THE SNAPSHOT

Led by two Dal psychologists, the offers free care to low-income Nova Scotians while training clinical psychology PhD students to help meet growing demand in the province. With operational funding from Nova ScotiaŌĆÖs Office of Addictions and Mental Health, the centreŌĆÖs innovative service delivery model offers vital care to those in need while filling critical gaps in the system.

THE CHALLENGE

After exhausting his savings to launch a startup, the resulting stress was taking a mental and physical toll on ŌĆśFrank,ŌĆÖ a Halifax resident sharing his story anonymously. ŌĆ£I felt trapped in a cycle of worry,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£I lost weight and struggled with chronic insomnia. The financial strain made it hard to see solutions, and I didnŌĆÖt have the tools to manage my stress.ŌĆØ

Although Frank has a family doctor, the physician couldnŌĆÖt offer the support he needed. Without additional health insurance or the means to pay out of pocket to visit a private psychology clinic, he was initially unsure where to turn. ItŌĆÖs a struggle faced by thousands of Nova Scotians searching for affordable ways to access the psychological help they need.

On the other side of the patient-client equation there is another challenge. Students must complete more than 1,000 clinical training hours over the course of their studies but often have difficulty finding places to practice. ŌĆ£There isnŌĆÖt always a good fit for students that are early in their training,ŌĆØ says Dr. Shannon Johnson, director of clinical training for DalŌĆÖs clinical psychology PhD program. ŌĆ£We really wanted the ability to offer more of that training internally.ŌĆØ

THE SOLUTION

Drs. Alissa Pencer, left, and Shannon Johnson are taking pressure off Nova ScotiaŌĆÖs mental health system with their innovative clinic.

Dr. Johnson and Dr. Alissa Pencer, the programŌĆÖs field placement coordinator, had previous experience with the Dalhousie School of╠² Social Work Community Clinic, which offers interdisciplinary health students the chance to care for clients from low-income and marginalized communities. ŌĆ£That really stood out to us as a unique experience that our students donŌĆÖt tend to get in other settings,ŌĆØ says Dr. Pencer.

Inspired by the social-work model, the psychologists saw an opportunity to align the needs of communities underserved by psychological services and the students who could provide them. They began planning a community-based psychology clinic focused on clients facing barriers to care.

That vision was supported by Nova ScotiaŌĆÖs Office of Addictions and Mental Health, which provided three years of operational funding. In September 2023, the Dalhousie Centre for Psychological Health officially opened its doors in HalifaxŌĆÖs Fenwick Medical Centre.

The Honourable Brian Comer. Minister for Addictions and Mental Health speaks at the centreŌĆÖs opening.

THE WORK

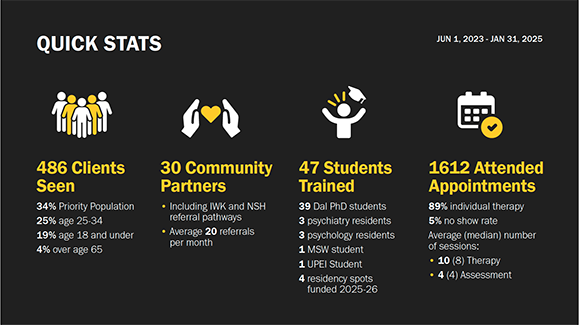

Since opening, 47 PhD students and residents have provided care as part of their training, under the supervision of the centreŌĆÖs eight psychologists, including Drs. Johnson and Pencer, the centreŌĆÖs co-directors. Also on staff are a dedicated health outcomes scientist and research lead, two social work team members, a clinic manager, and several student staff members in intake and front desk positions.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs not just that weŌĆÖre adding to what the public system is already doing,ŌĆØ says Dr. Pencer of the centreŌĆÖs holistic approach. ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖre providing some services that you canŌĆÖt get anywhere else in a public clinic.ŌĆØ

One of those unique offerings is the presence of a case manager and service navigator who work with clients on meeting needs that canŌĆÖt be addressed in therapy, such as accessing housing, food, education, or career-related resources.

ŌĆ£As you can imagine, not knowing where your next meal is going to come from is very distracting and can significantly impact your ability to engage in therapy and implement the skills youŌĆÖre learning in between sessions,ŌĆØ says Janelle Duguay, the clinicŌĆÖs case manager and a social worker who helped Frank apply for Employment Insurance benefits.

Delivering culturally-informed care is also a priority. The clinic has been working with Indigenous social worker Anangkwe Charity Fleming to adapt cognitive behavioural therapy for clients referred by the MiŌĆÖkmaw Native Friendship Centre.

Clinically relevant research is another focus. Students and staff engage in research that addresses questions that arise from the centreŌĆÖs work with low-income and diverse clients. ŌĆ£Much of the existing research is not inclusive of the populations served at the centre, so there are clear opportunities to conduct research in real time to have an immediate impact on clinical services in the Centre for Psychological Health,ŌĆØ says Dr. Debbie Emberly, the clinicŌĆÖs health outcomes scientist and research lead.

THE IMPACT

Frank says that taking part in eight therapy sessions helped him regain control of his life.

ŌĆ£I now approach problems with clarity, and IŌĆÖm no longer overwhelmed by worry like before,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£The Centre for Psychological Health gave me back a sense of agency over my mind and my circumstances. IŌĆÖm grateful for their holistic approach ŌĆö therapy addressed my mental health, while case management tackled practical needs like securing EI. ItŌĆÖs a model that truly considers the whole person.ŌĆØ

Offering assessment and intervention services, the centre has so far delivered over 1,600 individual appointments to nearly 500 clients aged five to over 65 referred by 30 different community partner organizations.

I now approach problems with clarity, and IŌĆÖm no longer overwhelmed by worry like before

The has referred more than 20 clients to the centre. ŌĆ£The relationship we have built with their team has been based on them being culturally informed and non-harmful in their practices,ŌĆØ says Friendship Centre mental health counsellor Kendall Paul, noting that many of the people referred are Two-Spirit and non-binary. ŌĆ£TheyŌĆÖve always been open to meeting clients where theyŌĆÖre at.ŌĆØ

Fifth-year clinical psychology PhD student Catrina MacPhee has been involved with the centre since it opened, supervising first- and second-year students and serving as an intake clinician. ŌĆ£The centre provides a unique learning opportunity to support individuals from varied backgrounds with a range of mental health challenges,ŌĆØ says MacPhee.

Originally from Cape Breton, MacPhee is interested in treating anxiety and mood disorders and plans to practice in Nova Scotia after her residency.

Brianna Boyle was the clinicŌĆÖs first psychology resident.

Fellow Nova Scotian Brianna Boyle was the clinicŌĆÖs first psychology resident and plans to practice in her home province after finishing her PhD studies at the University of New Brunswick. Additional residents will be coming to Dal this fall as part of four new clinical psychology residency seats announced by the province last year.

ŌĆ£Being able to work with children, youth, adults, and older adults across the lifespan has been fantastic, especially for groups that are often underserved and underrepresented,ŌĆØ says Boyle. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs been very enriching for my own learning and being able to give back to the community that I consider home is very important.ŌĆØ