The ocean holds 90 per cent of the Earth’s carbon and has absorbed 40 per cent of fossil fuel emissions to date. It’s a sink for CO2 that removes more of the greenhouse gas from the atmosphere than all the rain forests on Earth combined.

The ocean’s supreme power for carbon sequestration has drawn Transforming Climate Action researchers to focus on it as a potential gamechanger in the fight against global warming. They’re hoping to learn if the ocean’s natural abilities to absorb CO2 from the atmosphere can be amplified to help us meet net zero carbon targets by 2050 and avoid the worst impacts of a hotter planet.

An antacid for the ocean

To do this, the researchers are testing the possibility of adding magnesium hydroxide to the ocean. Magnesium hydroxide is the main ingredient in the antacids we use to treat heartburn and upset stomach. It’s an alkaline substance that raises pH levels when mixed with ocean water and spurs a chemical reaction that promotes the absorption of CO2.

While the scientists explore the feasibly of this approach, oceanographer Dr. Hugh MacIntyre and his students are leading a parallel project to ensure interventions made in the ocean are safe for the creatures that call it home. To do this, they’re focused on phytoplankton, the extremely small plant-like organisms that are at the foundation of the ocean’s food web.

Transformational Climate Action

Emerging science reveals the ocean's ability to absorb CO2Ěýand regulate temperatures is changing in ways we don’t understand. These critical shifts are not accounted for in climate targets – a risk we can no longer take. With support from the Canada First Research Excellence Fund , pilipiliÂţ» is leading an ocean-first approach to tackle climate change and equipping Canada with the knowledge, innovations, and opportunities to secure a positive climate future.

.

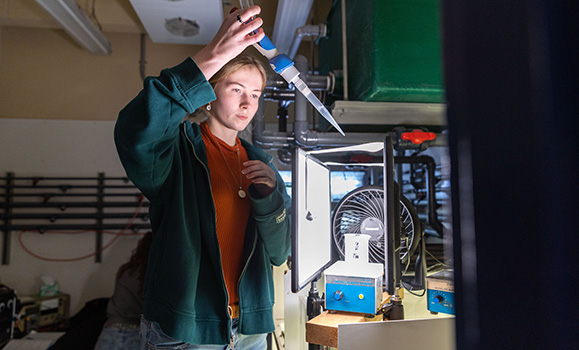

Dr. Macintyre’s students test the resilience of phytoplankton

It comes down to the phytoplankton

“Pretty much everything in the ocean eats something, that ate something, that ate phytoplankton,” says Dr. MacIntyre. “Right whales eat copepods that eat phytoplankton. Cod eat smaller fish that eat the phytoplankton, and so on.”

If phytoplankton are harmed, things go wrong very quickly in ocean ecosystems, which is why the researcher says, they are so important to study. To test if CO2Ěýremoval techniques have unintended negative consequences, MacIntyre and his team are running a series of experiments exposing phytoplankton to magnesium hydroxide.

Water samples containing phytoplankton test subjects.

Water samples containing phytoplankton test subjects.

The unknowns of alkalinity

For billions of years, rock erosion from rivers and other sources has dispersed alkaline substances like magnesium hydroxide into the ocean’s waters. But it is a slow process. TCA researchers are exploring the possibility of speeding up the process dramatically by adding the molecule in massive quantities by artificial means.Ěý

Adding alkalinity also has the potential to reverse acidification of the ocean which has taken place since the beginning of the industrial revolution. CO2Ěýin the atmosphere, caused by the burning of fossil fuels, has caused a 30 per cent increase in ocean acidity, much to the detriment of many ocean ecosystems

Adding a dose of magnesium hydroxide.

Adding a dose of magnesium hydroxide.

“There is a massive amount of literature on acidifying the ocean, and its damaging impact,” says Dr. MacIntyre. “But there is a surprisingly small amount of literature on raising pH with alkaline substances and its effect on phytoplankton growth.”

He and his research group intend to change this: “The question is, if you affect the pH around the phytoplankton, will you affect what's going on inside the cell,” he says. “We want to know if they can accommodate a rise in pH, or will they actually be harmed by it.”

Also in this series

Ěý

Transforming Climate Action: Where the atmosphere and ocean meet