Scientists are getting a glimpse into a two-million-year-old ecosystem in northern Greenland with the help of ancient DNA they extracted from deep sediment that had built up over 20,000 years, been preserved in ice and remained untouched by humans.

The discovery of two-million-year-old microscopic fragments of environmental DNA, or eDNA, in sediment from the Ice Age breaks a long-standing record and ushers in a new chapter in the history of evolution.

Using cutting-edge technology, researchers from Dalhousie and several European institutions determined the fragments are one million years older than the previous record for DNA sampled from a Siberian mammoth bone. They hope the results could help predict the long-term environmental toll of today’s global warming.

John Gosse, a geoscientist in Dal's Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences and the CRISDal (Cosmic Ray Isotope Sciences at pilipiliÂţ») Lab, helped date the sediments through geochronometry, the measure of geological time to, for instance, date past meteor impacts, eruptions, earthquakes or, in this case, when sediment was deposited by a stream that no longer exists.

John Gosse, a geoscientist in Dal's Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences and the CRISDal (Cosmic Ray Isotope Sciences at pilipiliÂţ») Lab, helped date the sediments through geochronometry, the measure of geological time to, for instance, date past meteor impacts, eruptions, earthquakes or, in this case, when sediment was deposited by a stream that no longer exists.

He says the amalgamation of different dating methods, including a molecular clock based on DNA, helped improve our knowledge of this important site, and reveals a time when the Greenland Ice Sheet was at a position similar to today.

"In 2014, we were asked to date samples that the Danish team had collected at Kap København, near the northern tip of Greenland. The geochronometry was challenging because no single technique could provide a precise date for the deposition of sediment with the eDNA. Combined, the dating methods suggest a most probable age of about two million years,” says Dr. Gosse, shown above right.

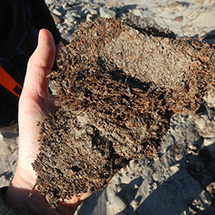

Close-up of organic material in the coastal deposits. The organic layers show traces of the rich plant flora and insect fauna that lived two million years ago in Kap København in North Greenland. (Credit: Professor Kurt H. Kjær)

A new chapter opens

During each of more than 20 subsequent glacial and interglacial cycles, the estuarine sediment was covered by more sediment and eventually raised above sea-level, frozen, then incised by more recent estuary channels, and sampled for geochronology and eDNA. Â

Dr. Gosse says that advances by the Globe Institute at the University of Copenhagen in extraction of the most resilient DNA from clays in the sediment, allowed the team to extend the DNA record to such a long time ago.

“It’s not Jurassic! But the fingerprints of co-existing terrestrial and aqueous plants and animals have been documented in the Arctic at an interesting climatic period.”Â

The discovery was made by a team of scientists led by Eske Willerslev of the University of Cambridge and the Lundbeck Foundation GeoGenetics Centre and Kurt H. Kjaer of the Lundbeck Foundation.

“A new chapter spanning one million extra years of history has finally been opened and for the first time we can look directly at the DNA of a past ecosystem that far back in time,” Prof. Willerslev says of the findings, published in the journal Nature.

“DNA can degrade quickly, but we’ve shown that under the right circumstances we can now go back further in time than anyone could have dared imagine.”

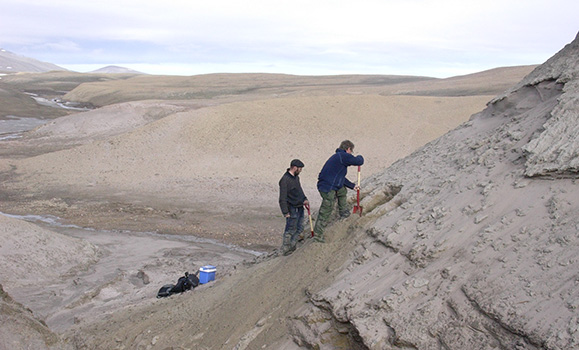

Professors Eske Willerslev and Kurt H. Kjær exposing fresh layers for sampling of sediments. (Credit: Professor Svend Funder)

In the mouth of a fjord

The incomplete samples, a few millionths of a millimetre long, were taken from the Kap København Formation, a sediment deposit almost 100 metres thick tucked in the mouth of a fjord in the Arctic Ocean in Greenland’s northernmost point. The climate in Greenland at the time varied between Arctic and temperate, and was between 10° to 17°C warmer than Greenland is today.

Scientists discovered DNA evidence of animals, plants and microorganisms, including reindeer, hares, lemmings, birch and poplar trees. Researchers even found that mastodon, an Ice Age mammal, roamed as far as Greenland before becoming extinct. Previously it was thought the range of the elephant-like animals did not extend as far as Greenland from its known origins of North and Central America.

"The DNA and other evidence indicates that two million years ago, northern Greenland had a warmer climate and associated ecosystem than today — there were trees! — but also that the site was colder than the 3.9 million-year-old sites that Canadian and other researchers have been studying in the Canadian High Arctic on Ellesmere Island," says Dr. Gosse.

Detective work by 40 researchers from Denmark, the UK, France, Sweden, Norway, the U.S., Canada and Germany unlocked the secrets of the fragments of DNA. The process was painstaking – first they needed to establish whether there was DNA hidden in the clay and quartz, and if there was, could they pilipiliÂţ»fully detach the DNA from the sediment to examine it? Eventually, the answer was yes.

The researchers compared every DNA fragment with extensive libraries of DNA collected from present-day animals, plants and microorganisms. A picture began to emerge of the DNA from trees, bushes, birds, animals and microorganisms.

Shown above right: Newly thawed moss from the permafrost coastal deposits. The moss originates from erosion of the river that cut through the landscape at Kap København some two million years ago. C(redit: Professor Nicolaj K. Larsen)

Endless possibilities

The two-million-year-old samples will also help academics build a picture of a previously unknown stage in the evolution of the DNA of a range of species still in existence today.

"DNA generally survives best in cold, dry conditions such as those that prevailed during most of the period since the material was deposited at Kap København. Now that we have pilipiliÂţ»fully extracted ancient DNA from clay and quartz, it may be possible that clay may have preserved ancient DNA in warm, humid environments in sites found in Africa," Prof. Willerslev explained.

"If we can begin to explore ancient DNA in clay grains from Africa, we may be able to gather ground-breaking information about the origin of many different species — perhaps even new knowledge about the first humans and their ancestors. The possibilities are endless.”

Dr. Gosse suggests the next steps might be to learn how different those ecosystems are from those in similar climate regimes today, and for paleontologists and paleo-biologists to assess the ancient food chains and how those ancient flora and fauna may have evolved over two million years.

“I wonder how the Kap Kobenhavn mastodons differed from the those found in more recent ice-age sediment in Nova Scotia,” he says.

The CRISDal team is leading the Pliocene Landscapes and Arctic Remains—Frozen in Time, or PoLAR-FIT, exhibition next summer, when they will take the Globe Institute collaborators to even older sediment records in the Canadian High Arctic.

To read the full Nature article, visit https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-022-05453-y

An artist’s reconstruction of the landscape surrounding the Kap København formation today. This arctic desert is one of the coldest and driest environments, which is reflected in the low biodiversity and production. (Credit: Beth Zaiken)

Nova Scotia Research and Innovation Trust (NSRIT) supports research infrastructure in Nova Scotia by matching national funding from the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI). NSRIT benefits researchers in areas such as Health and Life Sciences, Ocean Technology, Clean Technology, and Communications and IT technology. Since 2001, NSRIT – through the Province of Nova Scotia – has awarded over $66 million to more than 340 projects at Nova Scotia research beneficiary institutions, dramatically leveraging opportunities for innovation and direct economic benefits to the people of Nova Scotia and beyond.