âA deeply generous and honest gift to the world.â

Thatâs how Nova Scotia-born actor and filmmaker Elliot Page describes , multidisciplinary artist Vivek Shrayaâs 2022 book â a manual of sorts that promises to let âreaders in on the secrets to a life of reinvention.â

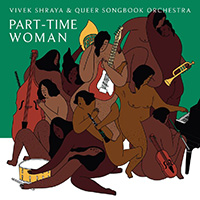

Shrayaâs courageous quest to share her own story as a trans person and advocate for others has taken many forms from music, film and theatre to visual arts and fashion. The accolades for her work are never far behind their release into the world: Shrayaâs best-selling 2018 book was heralded by Vanity Fair as âcultural rocket fuel,â her album was nominated for the Polaris Music Prize in 2018, and her one-person debut play, , is now being turned into a TV series.

When sheâs not creating herself, Shraya â a seven-time finalist âworks to support emerging BIPOC writers via her award-winning publishing imprint, , and serves as director on the board of the n â an organization that seeks to improve the lives of LGBTQ+ women and girls.

Shraya was the third speaker in Dalâs Viola Desmond Legacy Lecture series, a four-part initiative that grew out of the Year of Belonging speaker series held throughout Dalâs 200th anniversary year. Viola Desmond, the lecture seriesâ namesake, was infamously convicted of tax evasion as punishment for refusing to change seats in a movie theatre in 1946 and became a civil rights icon.

Shrayaâs lecture took place virtually on Tuesday, Nov.15 from 7-8:30pm (AST). The event included a Q&A session moderated by , the James R. Johnston Chair in Black Canadian Studies at Dal and was hosted by Dr. Theresa Rajack-Talley, Dalâs vice-provost equity and inclusion.

Below, watch Shraya's lecture and learn more about her story through five interview excerpts:

She first learned about transness in her 20s.

Ìę

Shraya came out as transgender on February 15, 2016, at age 35, publicly sharing her decision to use she/her pronouns on Facebook that day. In an , she describes when she first learned about transness:

"The first time I learned about transness, I was in my early/mid twenties. I remember wishing that I had been presented with the option when I was younger. It felt like a ship that had sailed. I remember wishing that I had been presented with the option when I was younger. It felt like a ship that had sailed.

After a solid decade of experiencing daily genderphobia and homophobia that I experienced in school, my early twenties was also a period of time when I was very focused on adopting masculinity. I often talk about how it was my motherâs love that prevented me from killing myself as a teenager, which is true, but choosing to live was an act of surrendering to masculinity. I even told myself that becoming a man could be a kind of fun challenge.

But the longer I have lived, the more painful the enforcement of masculinity has felt, especially as I have developed friendships with people who have been eager to celebrate me for who I am. So in a lot of ways, I see my transition as more of a âde-transition,â trying to undo the work I did to survive.â

She transformed anonymous hate mail into a comic book.

Ìę

, a collaboration with visual artist Ness Lee, illustrates a string of transphobic hate mail Shraya began receiving in her inbox in the fall of 2017. She described the broader cultural discussion she aimed to spark in an :

"A couple of years ago when people would say something hateful on the Internet they would like block out their name and they wouldn't use the image. You could always tell who a troll was on Twitter.

âBut increasingly there are no systems in place to really protect people from being trolled. I find that trolls no longer have to be anonymous or care about their anonymity."

âI would love this book to be part of a broader conversation. Instead of just subscribing to this 'turn the other cheek' approach to trolling, we should continue to think about better ways to be addressing hateful behaviour on the Internet."

Above image courtesy of Arsenal Pulp Press.

Her photo essay Trisha features vintage photos of her mother recaptured with Vivek as the subject.

Ìę

Shraya on the genesis of her powerful photo essay in Canadian Art a year after its release: "In the spring of 2015, Toronto multidisciplinary artist Casey Mecija and I were jointly touring our short films. Hers features her father, and mine features my mother. My presentation always included a photo of my mom, at which I would point and say, 'Itâs strange to see how much I resemble her now.'

One aspect of the creative process that I find marvellous is never knowing when an idea is gestating. It was likely the repetition of this comment throughout our tour that planted the idea of Trisha, a project in which I investigated this resemblance through the recreation of several vintage photos of my mother taken during her honeymoon in Jasper, with me replacing her as subject."

Alongside the images, Shraya reflects on her relationship with her mother in : âYou had also prayed for me to look like Dad, but you forgot to pray for the rest of me. It is strange that you would overlook this, as you have always said âBe careful what you pray for.â When I take off my clothes and look in the mirror, I see Dad's body, as you wished. But the rest of me has always wished to be you.â

Image courtesy of

Iâm Afraid of Men explores the toll toxic masculinity took on her life.

Ìę

In her , Vivek Shraya provides an intimate glimpse into the damaging impacts of misogyny, homophobia, and transphobia on her life. She whatâs behind the bookâs title and message:

"I put out an album in 2017 called Part-Time Woman, and in that album, I hadwritten a song called âIâm Afraid of Men,â which was inspired by me thinking about how, even before transition, I had feared men. [This fear] had basically impacted my life in countless, often harmful, ways. Writing the song was a way to just be really forthcoming about this history with men, and the book sort of grew out of it as a way to delve deeper into some of the themes I was exploring.

Toward the end of the book, I begin to sort of turn the title on its head by speaking to the ways that, actually, the experience of fear is a cycle. Men â and sometimes, women â fear me. And instead of managing and thinking about that fear, often the immediate response has been to harass or to harm. I actually think fear and discomfort are fine responses; I think itâs how we manage our fears and discomfortâthatâs what Iâm trying to target . . . It was actually the bookâs editor, David Ross, who suggested we put âMen Are Afraid of Meâ on the back cover. Part of the rationale was thinking about the book as art, and as an object that will, hopefully, travel. What does it mean for this book to be carried in public spaces? What might it mean to have the front and back cover agitate in these public spaces? As soon as he suggested it, I was like, 'Yes.'"

She has described moving back to her home province of Alberta to teach creative writing as a healing experience.

Ìę

In 2019, Shraya left Toronto for Calgary â returning to the province where she grew up as one of two sons of Indian immigrants. She took up a post teaching creative writing as an of English at the University of Calgary, a position that proved personally impactful.

âI was really nervous moving back to Alberta because of my experience with homophobia growing up in Edmonton,â she in 2019. âBut, truthfully, I feel like I have won the lottery. Teaching in Alberta has been healing for me.â