In late March 2022, Dr. David Kelvin was in Kigali, Rwanda, preparing to give the keynote address at a conference on how to best use science and technology to mitigate challenges linked to the COVID-19 pandemic. His talk would focus on vaccines and the future for developing countries using the pandemic as a case study.

Dr. Kelvin, a professor in Dalhousie's Department of Microbiology and Immunology, would also take the opportunity to review major projects in the east and central African country, including one on the spillover of emerging infectious diseases from non-human primates into humans and vice versa.

While there, however, word emerged that a mosquito-borne virus, most commonly seen in domesticated animals in sub-Saharan Africa, was spreading rapidly through Rwanda, afflicting cattle, sheep and goats as well as humans. Rift Valley Fever Virus — a zoonotic virus — was tearing through livestock, threatening one of the country's main sources of revenue and the domestic food supply.

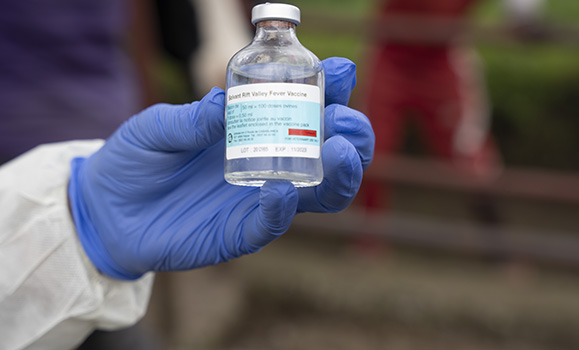

Dr. Kelvin and his research fellow, Dr. Pacifique Ndishimye (shown at right), decided to launch multiple studies and initiatives that would assess the efficacy of the current RVFV vaccine for cattle, build a better vaccine and determine how the disease actually affects the immune system prior to death.

Dr. Kelvin and his research fellow, Dr. Pacifique Ndishimye (shown at right), decided to launch multiple studies and initiatives that would assess the efficacy of the current RVFV vaccine for cattle, build a better vaccine and determine how the disease actually affects the immune system prior to death.

They would also help with a widespread vaccination program aimed at protecting cattle and other ruminants against the virus, which was also being reported in neighboring countries, such as Burundi, Kenya and Uganda.

"This is a huge outbreak, so we started several projects and one was to follow the vaccination of animals to answer questions similar to those we asked of the COVID vaccine—- what is the efficacy of the vaccine, how many animals are actually protected and what is the durability of the vaccine," says Dr. Kelvin.

"This is a disease that has huge implications for a small country."

An understudied virus

The pair settled in for more than two months, concentrating their efforts in three districts near Lake Mugesera where the first cases were reported. Working with local scientists from the University of Rwanda, Rwanda Agriculture and Animal Resources Development Board and the Rwanda Biomedical Center, they collected blood samples from both suspected and/or infected cattle, sheep and goats, and people, water sources and mosquitos. They also helped vaccinate thousands of cattle on farms dotting the countryside.

The data from those samples will help indicate whether the vaccine is working by identifying the immunological signatures of RVFV vaccine effectiveness. They will also identify key immune pathways that provide optimal vaccination in animals, which will help develop an improved vaccine in the future.

Today, two live attenuated vaccines produced in Morocco (RIFTOVAX-LR and RIFTOVAX-SR) are being administered in Rwanda. There remains no approved human vaccine to protect against infection caused by RVFV, and rapid testing capacity is limited and economically exclusive.

"This will be one of the first studies to be done on this virus," says Dr. Ndishimye, who is from Rwanda.

"We are trying to understand the virus and also trying to understand the vaccine because there is evidence that even the animals that have been vaccinated are getting infected."

Understanding the dynamics of virus spread

Discovered in the 1930s, RVFV can infect domesticated animals. It often causes abortions in pregnant cattle and can cause fatal hemorrhagic disease in about 10 to 20 per cent of animals.

Humans can be infected through contact with bodily fluids from infected animals, which can occur on farms, butcheries or other sites where people are working with contaminated meat. Human infection can lead to fatal hemorrhagic disease in about two per cent of the cases, but the mortality rate goes up to 50 per cent with more severe disease. People can also contract it through consuming infected meat or being bitten by an infected mosquito, which typically causes flu-like symptoms.

Ěý

Ěý

Dr. Kelvin says he visited one farm where an infected cow suffered an abortion, finding that some of the farmhands that helped her later contracted RVFV.

"We are now working with local scientists and policy makers to develop an early warning system that will alert officials to a potential zoonotic outbreak. That will allow farmers, for example, to use their cellphones to report abortions among their cattle — a sign of a potential hemorrhagic viral outbreak," he says.

This early warning system will also be linked to available satellite images and weather/climate forecasting data. Their preliminary analysis, which was done based on the available satellite data on rainfall and temperature, has confirmed that RVFV outbreaks in eastern Africa are closely associated with periods of heavy rainfall that occur during the warm phase of the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) phenomenon, which affects the mosquito populations acting as vectors and reservoirs of the disease.

“We believe that this system will enable national authorities to implement measures to avert RVF impending epidemics," says Dr. Ndishimye.