When Jim Prosper was born in 1925, his mother was eighteen and not married. As was common for a young woman in that situation at the time, she gave up her son for adoption. Jim lived the first five years of his life in a Halifax orphanage, and in 1930 became a resident of the Indian Residential School in Shubenacadie, which was the same year it opened. He lived there until he was 18.

When Jim Prosper was born in 1925, his mother was eighteen and not married. As was common for a young woman in that situation at the time, she gave up her son for adoption. Jim lived the first five years of his life in a Halifax orphanage, and in 1930 became a resident of the Indian Residential School in Shubenacadie, which was the same year it opened. He lived there until he was 18.

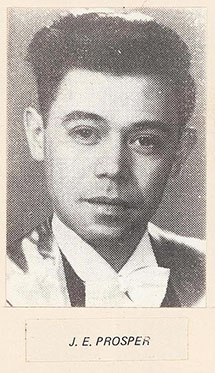

Upon leaving the residential school, Jim, a proud MiŌĆÖkmaw, served in the Second World War. When he returned to MiŌĆÖkmaŌĆÖki, Jim attended St. Francis Xavier for two years to study engineering, followed by two more years at the Nova Scotia Institute of Technology (which later became the Technical University of Nova Scotia and then DalhousieŌĆÖs Faculty of Engineering) to complete his engineering degree. Jim is believed to be the first Indigenous engineering graduate from both institutions.

Right: Jim ProsperŌĆÖs 1952 graduation photo from the Nova Scotia Institute of Technology.

After a distinguished career that included being a lead engineer on Cold War intelligence projects, Jim retired in 1984. It was during this period of retirement that Jim decided to spend his time researching his genealogy in the hope of learning more about his mother and finding anything he could about his father. He made many visits back to the East Coast from his home in Ottawa, travelling to First Nations communities in the region and talking with the people who lived there.┬Ā

Through his visits, Jim eventually learned who his motherŌĆÖs family was, meeting people who knew his mother and who could also tell him about his father ŌĆö believed to be an American sailor. When he visited these communities and got to know the people, Jim kept hearing the same thing everywhere he went: ŌĆ£This reserve is shrinking, the land is being taken away.ŌĆØ

This topic ignited a passion in Jim, and he soon became an ardent researcher of colonialism, aboriginal treaties, rights, and sovereignty. ThatŌĆÖs when he began curating an impressive book collection ŌĆö one that has now found a new home at pilipili┬■╗Ł.

ŌĆ£My father was the hardcopy Google before Google,ŌĆØ says Ron Prosper, one of JimŌĆÖs three grown children. ŌĆ£For my dad, it was important to have hard copies of everything. He never got into digital, and he never wanted to leave information behind. He had to own the book; it wasnŌĆÖt enough that he could borrow it from a library.ŌĆØ

Book dealers on ŌĆśspeed dialŌĆÖ

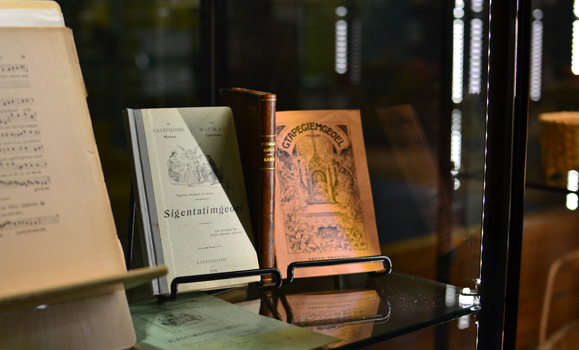

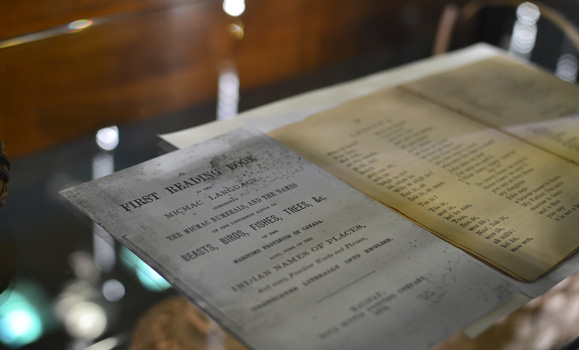

Jim amassed his extraordinary book collection over twenty years, dealing with some of the most well-known antiquarian book sellers in Canada. ŌĆ£He had antiquarian book dealers on speed dial,ŌĆØ says Ron. The most unique books in JimŌĆÖs collection are bibles, hymnbooks, and catechisms in MiŌĆÖkmaq, some dating to the late 1800s.

Eventually, JimŌĆÖs book collecting slowed down, and once he reached his nineties, it became challenging for him to continue living alone. His family helped him move to a seniorŌĆÖs residence ŌĆö where, at 97, he still lives ŌĆö and then came the difficult job of packing up the homestead.

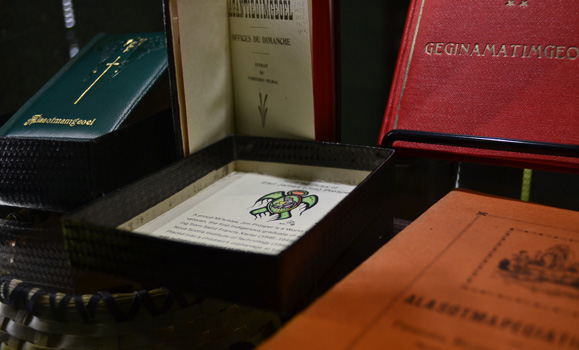

Left: The bookplate that appears in all donated books. Artwork by Chelsea Brooks, Indian Brook Reserve.

Ron knew his fatherŌĆÖs book collection was special, having seen how much love and effort he had put into curating it. ŌĆ£I knew that if the collection was ever going to survive intact, there were very few institutions that would have the capacity to take it on. I felt that a university, being an institution devoted to learning, would be the best place for the collection. I also wanted to take it somewhere close to my fatherŌĆÖs birthplace, and that was how I decided upon donating the collection to Dalhousie,ŌĆØ says Ron.

Exceedingly rare and old

Phil Laugher, a digital asset technician in the Dalhousie Libraries with a twenty-two-year background in the antique book trade, assessed JimŌĆÖs collection and says it is one of the most thorough heŌĆÖs ever encountered. ŌĆ£This collection was developed through a meticulous effort. It was a true labour of love in both the quality and quantity of the materials. There are 100-year-old items in pristine condition, and in some cases, only two other libraries in the world have some of these titles,ŌĆØ says Laugher.

The exceedingly rare and old books will be securely housed in Dalhousie Libraries Special Collections, while the more contemporary books will be found on the shelves in the newly launched Indigenous Community Room, found on the first floor of the Killam Memorial Library in the Gord Downie and Chanie Wenjack Legacy Space. The room, collaboratively designed with members of the Indigenous community at pilipili┬■╗Ł, creates a welcoming gathering place for Indigenous students, staff, and faculty to host and attend Indigenous ceremonies and events.┬Ā

The exceedingly rare and old books will be securely housed in Dalhousie Libraries Special Collections, while the more contemporary books will be found on the shelves in the newly launched Indigenous Community Room, found on the first floor of the Killam Memorial Library in the Gord Downie and Chanie Wenjack Legacy Space. The room, collaboratively designed with members of the Indigenous community at pilipili┬■╗Ł, creates a welcoming gathering place for Indigenous students, staff, and faculty to host and attend Indigenous ceremonies and events.┬Ā

ŌĆ£Things just could not have gone better,ŌĆØ Ron says, of the process of donating more than 700 books from his fatherŌĆÖs collection to the Dalhousie Libraries. ŌĆ£There were so many people with the right expertise working on this donation at pilipili┬■╗Ł, and the timing of the donation coinciding with the opening of the Indigenous Community Room in the Killam Library, itŌĆÖs all part of the wonderment of how this unfolded.ŌĆØ┬Ā

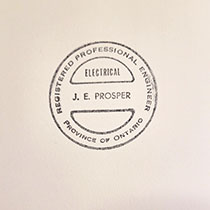

Above right: JimŌĆÖs personal stamp, which appears in many of the books he donated.

Jim was not able to travel to the official opening Indigenous Community Room on Tuesday morning where his collection was being introduced to the Dalhousie community, but Ron and some members of his family were honoured guests at the event, with Ron giving remarks about his father.┬Ā (Watch for coverage of the room opening later this week on Dal News)

ŌĆ£There is a unique story behind each of the collections that our donors give to the Dalhousie Libraries,ŌĆØ says Donna Bourne-Tyson, dean of Libraries. ŌĆ£The genesis of this particular collection and how it supported Jim ProsperŌĆÖs understanding of his family and his MiŌĆÖkmaq heritage makes it a very special and moving story. We are honoured to be entrusted with the preservation and sharing of this collection.ŌĆØ