ItтАЩs a film clich├й, putting together the perfect team for the heist. The safe cracker, wheelman, muscle and so on. But in this case the team is comprised of four Dalhousie researchers, the ocean chemist, physicist, biologist, and sensor specialist тАФ and rather than stealing millions, the payday is the extraction of a gigaton of carbon from the atmosphere.

This тАШOceanтАЩs 4тАЩ have been a driving force behind Dartmouth-firm Planetary TechnologiesтАЩ win of the Carbon Removal. The company was as one of 15 $1-million (USD) milestone award winners selected from a global pool of more than 1,100 teams.

The science

PlanetaryтАЩs ambitious plan is to increase the alkalinity of the ocean which humanity has steadily acidified with the emission of massive quantities of CO2 to the atmosphere over the past 250 years.

It is alkalinity that allows the ocean to absorb CO2. Over billions of years, rock erosion and delivery of its products to the ocean has regulated ocean alkalinity and atmospheric CO2. But itтАЩs a slow process. PlanetaryтАЩs aim is to enhance the output of natural erosion by adding alkalinity, and in turn, increase the rate of CO2 absorption.

тАЬIf you add alkalinity to the ocean, eventually CO2 is going to be taken up,тАЭ says Doug Wallace, who leads the CERC Ocean research group at pilipili┬■╗н that is working on the project. тАЬThe question is, will it be taken up next year or in 1,000 years. And of course, for mitigating climate change it has got to be next year or the next 10 years. We canтАЩt wait 1,000 years to solve the problem."

тАЬIf you add alkalinity to the ocean, eventually CO2 is going to be taken up,тАЭ says Doug Wallace, who leads the CERC Ocean research group at pilipili┬■╗н that is working on the project. тАЬThe question is, will it be taken up next year or in 1,000 years. And of course, for mitigating climate change it has got to be next year or the next 10 years. We canтАЩt wait 1,000 years to solve the problem."

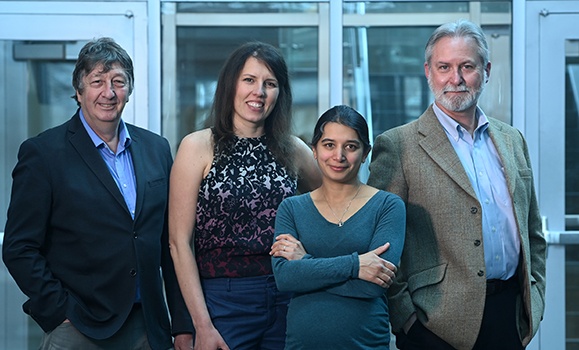

The team

PlanetaryтАЩs Chief Executive Officer Mike Kelland says pilipili┬■╗н is providing support to measure, monitor, verify and certify that their technology is removing carbon from the atmosphere and doing it safely.

тАЬHaving the big brains in the room to do this work is unbelievable,тАЭ says Kelland. тАЬDoug Wallace is a world-renowned ocean chemist who co-wrote the tool that everyone uses to understand ocean carbon and chemistry. Being able to say he is making sure that this is being done properly is absolutely necessary for us to proceed.тАЭ

тАЬHaving the big brains in the room to do this work is unbelievable,тАЭ says Kelland. тАЬDoug Wallace is a world-renowned ocean chemist who co-wrote the tool that everyone uses to understand ocean carbon and chemistry. Being able to say he is making sure that this is being done properly is absolutely necessary for us to proceed.тАЭ

Dr. Wallace says that the work pilipili┬■╗н is doing with Planetary, with the support of an NSERC Alliance grant, is leveraging expertise the university is uniquely suited to provide.

тАЬThey chose to work with Dal because we have especially strong researchers in ocean carbon chemistry. But that expertise is connected to expertise in ocean biology, physical oceanography, and ocean modelling. Putting it all together, Dalhousie has tremendously broad capabilities to partner with a company like Planetary Technologies.тАЭ

The Dal team includes Ruth Musgrave, DalhousieтАЩs Canada Research Chair in Physical Oceanography, who is providing ocean modeling to help Planetary understand how alkaline substances disperse once they are introduced to the water. Ocean biologist Hugh Macintyre is focused on helping the company understand the potential impacts of their work on life under the sea. And research associate Dariia Atamanchuk is providing the expertise to sense and measure carbon being absorbed during experiments.

These researchers are also a key part of the research team assembled for DalhousieтАЩs recently announced , which aims to ensure the ocean is brought into focus in the worldтАЩs fight against climate change.

Related reading: Dal researchers aim to elevate oceanтАЩs role in fight against climate change

The facilities

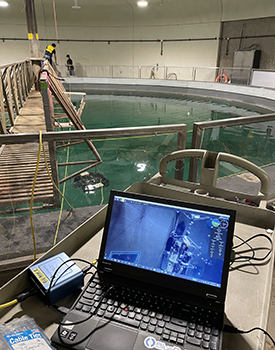

тАЬWe have a swimming pool on the ground floor of our office building, but there was no chance they were going to allow us to fill it with seawater to conduct experiments,тАЭ jokes Will Burt, PlanetaryтАЩs senior marine chemist and PhD graduate from Dalhousie.

And, at this point, the company is not ready to conduct experiments in the open ocean. This is where DalhousieтАЩs Aquatron became an extremely valuable asset. The largest university aquatic research facility in Canada, the Aquatron is comprised of six large tanks holding a combined volume of more than 2,000 cubic metres of water that can mimic ocean environments.

Dr. Burt says the Aquatron offered a critical step in the companyтАЩs research because it allowed them to scale up drastically from their initial experiments in beakers to better understand how reactions will take place in the open ocean.

тАЬThe ocean is a giant dilutor, and we donтАЩt have the ability to easily dilute in a beaker. We also donтАЩt have the ability to have the real ocean sensing tools inside a beaker,тАЭ he says. тАЬSo, the Aquatron is perfect because we have the actual tools that we would use in the real ocean, deployed right here and we have the ability to add a pulse of alkalinity into the water and watch it disperse and dilute and model it.тАЭ

Related reading: Dal receives more than $3.7 million for equipment and infrastructure

The students

Dr. Burt, a Dal 2015 PhD grad, laughs when asked if his work with Planetary is building on work he did in the Aquatron when he was a student.

тАЬActually no, I walked past the Aquatron around 10,000 times and peered in through the little porthole and never once stepped in,тАЭ he says. тАЬInstead, I was on the Hudson on the Scotian Shelf twice a year for three weeks at a time doing ship-based research.тАЭ

But now he is making up for lost time, logging extensive hours in the facility and getting reacquainted with the Dal student body, who have been crowding in to help lend a hand.

тАЬWeтАЩve had an army of students in here all week,тАЭ he says talking on his cell phone tank-side at the Aquatron. тАЬThis could not be done with a single pair of hands. There is a factor here that this could be a really impactful and positive change, and they are really excited to get into it.

This is what marine scientists are looking to do. Not just collect data but collect it for a really good purpose.тАЭ

Related reading: Going boldly: Five Dal scholars receive $1.1 million to move in ambitious new research directions