While Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield’s 2012/13 mission aboard the International Space Station (ISS) was capturing the imagination of star gazers around the world, he was capturing a view of planet Earth that only a handful of people have ever seen with their own eyes.

Actually, 13,199 different views of Earth, to be exact.

That‚Äôs how many of Hadfield‚Äôs personal photographs from his mission were donated to pilipili¬˛ª≠, making it one of two institutions in Canada to gain access to his incredible collection of shots showcasing our changing planet in all its blue, green, sandy and snowy glory.

PhD student Caitlin Cunningham, who works as an intern in Dalhousie Libraries’ GIS Centre, has spent the past year looking at every single one of those 13,199 images. Her mission with the Dal Libraries: to build a public digital archive that allows anyone and everyone to see the world the way Hadfield did.

Launching this week with an event on Thursday, April 11 at 3 p.m. in the Killam Library’s LINC (room 2600), the contains approximately 250 of Hadfield’s best shots of planet Earth. It’s designed as a “Story Map,” one that allows you to click on the photo’s location and see that part of the world through Hadfield’s lens, taken from 400 km above the planet’s surface.

“How many kids say, ‘I want to go to space, I want to be an astronaut’?” It’s one of those things that fascinates everybody,” says Caitlin. “To have the opportunity and the privilege to spend an entire year working with these photos taken from space was pretty cool; the seven-year-old in me was very happy.”

The power of maps

Caitlin first got into GIS — which stands for Geographic Information Systems — in her undergrad, though she says she always had an interest in maps and landscape planning. She used GIS software extensively in her Master of Environmental Studies degree at Dal, which focused on modeling better landscapes for honeybee sustainability.

Now, as an intern with the Dal Libraries GIS Centre — which manages Atlantic Canada's largest holdings of paper maps and atlases — she’s even more involved in the world of geography and mapping.

“You can basically make maps and analyze patterns at any kind of spatial scale,” she says about working with GIS software. “We’ve done work here looking at things on the city block scale to things on the global level… It’s really exciting because everybody can understand maps, and you can tell a lot of stories by connecting people to places they’re familiar with using a map.”

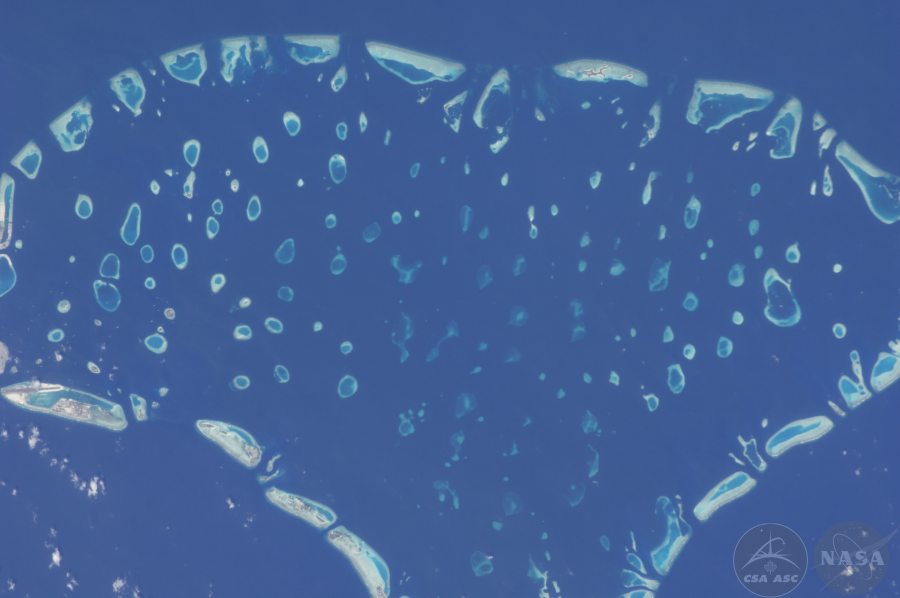

Maldives (Photo: CSA/NASA)

When GIS Specialist and Map Curator¬Ý James Boxall tapped Caitlin to oversee turning the Hadfield collection into a Story Map on behalf of the Dal Libraries, it represented months of work. Just sorting through the 13,000-plus images ‚Äî all shot by hand, many with a massive 400 mm lens ‚Äî to remove ones that were indistinct or blurry was a herculean task in and of itself. (The ISS moves at 17,000 km/h, after all.)¬Ý ‚ÄúI think I may be the only person on the planet who‚Äôs seen every photo,‚Äù said Caitlin.

Every photo was date and time stamped, and Caitlin was able to compare this data to the movements of the ISS to get an estimate as to where Hadfield may have been pointing his lens. From there, she looked for identifiable features — lakes, rivers, mountains, cities etc. — to try and figure out exactly what the image might be showing. In cases where Hadfield captured the same location multiple times, she tried to use the best or most interesting image, narrowing down the collection to a more manageable number for both her and site visitors.

“I tried to get photos from all over the world, though the space station has a trajectory that focuses more on some regions than others,” she explains.

Space — for everyone

The resulting Story Map has images from every continent except Antarctica. As you might expect, Hadfield’s home country was of particular interest in his lens, and there are photos of many Canadian cities and regions that you can view on the website. From Buenos Aires to Beijing, it’s a view of our world like no other.

The Story Map, accessible via the Dalhousie Libraries’ website, also contains a “Where in the World?” feature that aims to crowdsource the location for images that haven’t yet been identified. And there’s also a cool photo slider allowing you to see how Hadfield’s images reflect how the world has changed — and is continuing to change — before and after the astronaut’s time in space.

“I’m hoping the collection will help people think about the planet in a meaningful way,” says Caitlin. “Coming from a conservation background, this is a way to see the planet and to see the diversity of landscapes and how much of an impact humans have had on it. I don’t think there’s a single photo in the collection that you can’t see human impacts.”

While Hadfield is not able to attend Thursday’s event in person, he will be sending video greetings and representatives from his organization will be in attendance. He’s also given his enthusiastic support for Caitlin’s work. “We shared it with him and it was a big thumbs up,” she says.

She expects the skills she honed working on the Hadfield collection will be helpful with her interdisciplinary PhD, where she hopes to continue to work with a conservation lens: “How we can better live with other species and better plan landscapes,” as she puts it. And she’s proud of being a small part of Hadfield’s ongoing mission to bring science and space exploration to the masses.

“One thing Chris has said in some of his speeches is that getting to go to space is a privileged position, but what they’re doing up there is for everyone,” she says. “That’s really what this project is all about: it’s for everyone.”

View the full

Maritimes. (Photo: CSA/NASA)