Humans have harvested the ocean’s resources for millennia, but a new study published this week in the journal Science reveals, for the first time ever, a precise image of the massive scale of global fishing activity.

The study builds on a dataset that is hundreds of times more detailed than previous global surveys, showing that fishing covers at least 55 per cent of the ocean. That's four times the footprint of agriculture.

More than 40 million hours of fishing were observed in 2016 alone, with fishing vessels journeying more than 460 million kilometres during the year. That’s a distance equal to travelling to the moon and back 600 times.

By showing in detail where and when fishing takes place over time, the dataset offers a valuable glimpse into the positive role well-enforced policy can play in conservation and resource-management efforts. Â

“This clearly showed us that marine management on a large scale is possible,” explains Kristina Boerder, a Dal PhD student involved in the study.

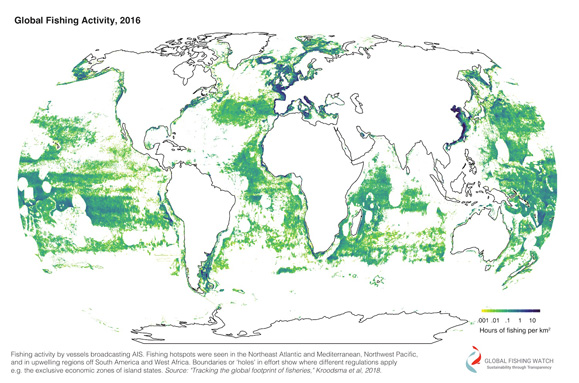

Global fishing activity, 2016, from the study.

View the digital map:

Boerder and fellow Dal ecologist Boris Worm are part of an international, multidisciplinary team that also includes researchers from sustainability advocacy group Global Fishing Watch, the National Geographic Society’s Pristine Seas project, the University of California Santa Barbara, Stanford University, aerial monitoring group SkyTruth and Google.

The team monitored the activity from more than 70,000 industrial fishing vessels between 2012 and 2016 using information beamed up to satellites from vessels’ automatic identification system (AIS) positions. AIS technology was first created to help prevent collisions between vessels in transit.

When viewed from space on a world map, the plotted data shows clearly how different fisheries management regimes such as exclusive economic zones and marine protected areas can regulate fishing activity.

“It’s working with national legislation and jurisdictions and the large protected areas when they are well set up and well enforced,” says Boerder. “That was really an eyeopener for us.”

Bringing transparency to an opaque industry

While many national governments already track fishing activity using similar methods, the data and technology developed as part of this study by Google engineers (with input early on from Computer Science researchers at Dal) and other partners is unique in one key way: .

That’s great news for academic researchers, conservation advocacy groups, consumers, and smaller governments that may currently lack ready access to such information.

It also holds particular value for agencies involved in ocean governance on the high seas in tough-to-track areas beyond national jurisdictions.

For instance, the dataset developed for this study shows that just five countries (China, Spain, Taiwan, Japan and South Korea) account for 85 per cent of the fishing observed in these remote parts of the ocean.

(Photo credit: Laurenne Schiller)

Boerder (pictured above) says such information offers a new level of transparency around commercial fishing, a traditionally opaque industry.

“We need to know what is going on to actually properly manage it. We need to have that understanding, overview and transparency,” says Boerder.

Understanding broader patterns

Another of the study’s key findings was that global fishing remains remarkably constant throughout the year.

While fishing bans and holidays were shown to have a big impact on activity, natural phenomenon such as climate patterns and fish migration seemed to have less of an influence.

The machine learning technology developed by the researchers enabled them to detect those ship positions and movements that represented fishing and also provided accurate information about vessel length, engine power and gross tonnage.

It also showed that vessels called longliners that catch tuna, billfish and sharks typically undertake the longest journeys, while purse seiners and trawlers generally operate on a regional scale.

With the study now published, the research team will continue making daily graphical overviews of global fishing activity available to the public.

And anyone is now able access live data about fishing activity in real time using the web tool.

“The most exciting part is just starting,” says Boerder. “There are just so many questions. We are pushing for better regulations and to integrate that data more and more, so having it publicly out there will really help.”