One of the most technologically adventurous exhibitions to emerge out of this year's packed slate of Halifax Explosion centenary offerings came about in a rather old-fashioned way: on a walk.

It was on this stroll through Shannon Park in Dartmouth a few years ago that Dal Architecture prof Brian Lilley and some colleagues noticed how close peninsular Halifax seemed from their vantage point across the harbour.

“We looked out across the Narrows and realized just how short that distance really was,” he says, referring to the strait that connects the outer Halifax Harbour with the Bedford Basin. “We started to imagine what two ships in that space would have been like.”

That’s the location where one hundred years ago this December 6 the Mont-Blanc, a French cargo ship packed with high-density explosives, collided with a Norwegian ship called the Imo, setting off what was the largest man-made explosion to take place before the advent of nuclear weapons.

The blast destroyed huge swaths of the northern portions of Halifax and Dartmouth, killing about 2,000 people and injuring an estimated 9,000 more. The force of the explosion itself, debris, fires, and collapsed buildings all contributed to the body count.

When Lilley and other members of the nascent , a creative interdisciplinary research group interested in exploring liminal urban spaces, set out on foot to some of the other Halifax Explosion sites, even bigger ideas began to emerge.

A mulitlayered, multidisciplinary journey

Walking the Debris Field: Public Geographies of the Halifax Explosion, an exhibition on now at the Dalhousie Art Gallery, is the result. Mixing architectural models, interactive technologies, found artifacts and even a dedicated smartphone app, the ambitious exhibition casts a radical new light on what is by now well-worn local history.

Rather than taking a strictly historical view of the explosion, the show takes viewers on a multilayered journey through the past and present urban geography of the explosion’s debris field — sometimes simultaneously.

“The interesting point for me now is to see what the effect of the explosion is on our current urban condition and in the way our society both commemorates and rectifies the scars and injustices of this giant catastrophe a hundred years ago,” says Lilley, whose NiS+TS collaborators included Barbara Lounder, Bob Bean and Mary Elizabeth Luka.

A piece called The Psychogeographer’s Table serves as an anchor for the show and a testament to the collaboration involved in the exhibition’s creation.

A finely milled tabletop landscape representing areas impacted by the explosion was made with the help of architecture students out of birchwood that was bleached to make it “as close to a bone as we possibly could,” says Lilley. Scorched timbers were added on the sides of the rectangular display for contrast and drawers pull out to reveal objects found during NiS+TS’s walks around the different neighbourhoods of the debris field. These found items, which can also be glimpsed through a slightly opaque glass portion of the tabletop meant to represent the water, include everything from simple shards of glass to a crushed iPhone case.

Digital integration

But it is the integration of digital imagery and holographic computing into the display that makes for a truly immersive experience. Lilley looked to Derek Reilly, head of the Graphics and Experiential Media (GEM) Lab in Dal’s Faculty of Computer Science and an expert in human-computer interaction, to make it happen.

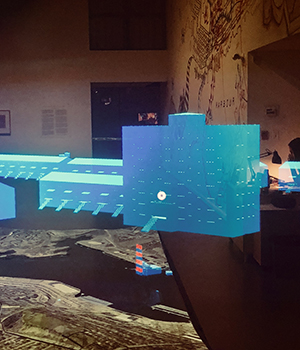

Dr. Reilly worked with graduate students in the GEM Lab, including doctoral candidate Juliano Franz and postdoc Joseph Malloch, as well as members of NiS+TS to fine-tune the approach and technical development of the displays, which include historic and current maps of the impacted areas projected precisely over the tabletop’s curvy contours and another element where exhibition goers don a wearable Microsoft HoloLens unit to explore inside virtual buildings superimposed on the table. Â

Dr. Reilly worked with graduate students in the GEM Lab, including doctoral candidate Juliano Franz and postdoc Joseph Malloch, as well as members of NiS+TS to fine-tune the approach and technical development of the displays, which include historic and current maps of the impacted areas projected precisely over the tabletop’s curvy contours and another element where exhibition goers don a wearable Microsoft HoloLens unit to explore inside virtual buildings superimposed on the table. Â

Certain textbook historians may take issue when they see images of today’s Irving Shipyard pop up next to a sugar refinery that was reduced to rubble in the explosion, but for Dr. Reilly it’s these cut-and-paste montages that best capture the spirit of NiS+TS and their walks.

“Through our discussions, our perspective changed a lot,” he says. “We were less interested in reproducing or representing the Halifax Explosion and more interested in allowing people to explore across space and time various elements of the city that correspond in some way or have some relation to the explosion that may not be immediately obvious."

The power of exploration

Similarly, a smartphone app called (designed in collaboration with local developer MindSea) allows users to explore the ruins and scarred landscapes — as well as stories and memories — in the debris field through a series of curated walks.

Like the table, the app encourages exploration and feedback — the very essence of the exhibition as a whole.

“Not everyone will have the same experience,” says Lilley, “and that’s very exciting, that there’s a multiplicity of narratives available through combining the layers.”

Walking the Debris Field is one of several exhibits that is part of the Dalhousie Art Gallery's current . The exhibition runs until Sunday, December 17. Learn more at