Mimi Cahill and her classmates have created a computer game. Unlike most games, this one was designed to help tackle one of the world’s most serious and challenging problems: the continued recruitment and use of child soldiers.

Like all students in the Informatics program, Mimi takes an Integrated Studies course each term that gives her the opportunity to work on a practical project. Working with teammates from her program, as well as Computer Science students (the course is cross-listed as Community Outreach for the Computer Science students), she’s made valuable contributions to several non-profit organizations.

For the fall term, Mimi chose to join five other students in wrapping up a computer game project that has spread across three terms over the past year. The game was built for the , a Dalhousie-based organization founded by retired Lieutenant-General Romeo Dallaire in 2007 that aims to progressively end the use of child soldiers through a security sector approach. It's designed to serve as an interactive training tool for security sector actors who may have direct contact with child soldiers.

“I sought this project out specifically, because I wanted a little bit of game-building experience and because it’s a meaningful project,” Mimi says, adding that she’s been interested in human rights and particularly child soldiers since she was about 13. “It’s a pretty deep subject, despite the fact that it’s a game.”

A training tool

According to Mimi, the project’s original purpose was to develop a game that would raise awareness about the plight of child soldiers, but evolved to focus on the training aspect. Recognizing that first-person interaction with child soldiers presents difficult choices and potential danger for security sector actors, subsequent groups chose to address the need for preparation.

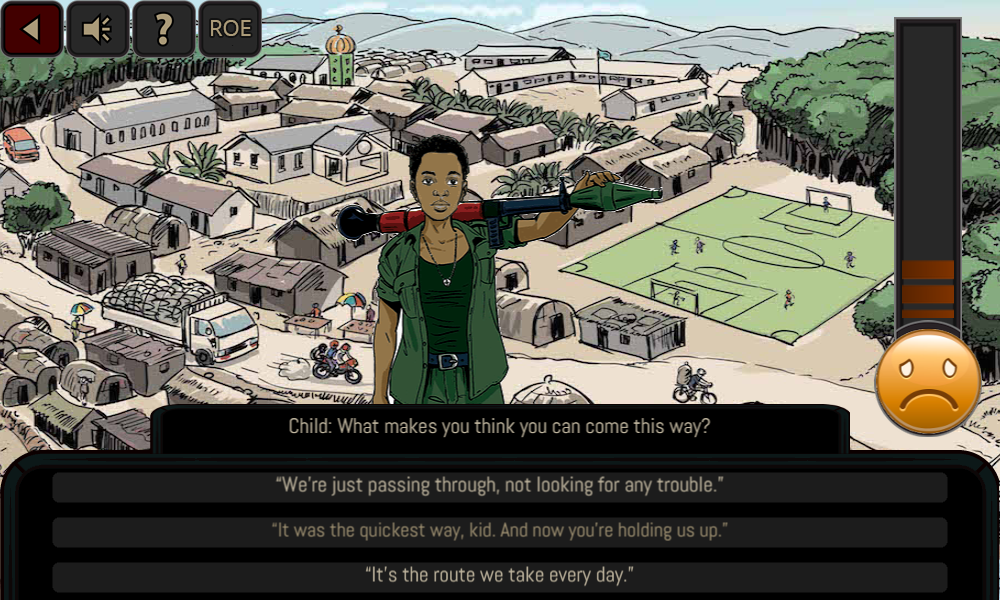

“The game is meant to be a training tool,” says Mimi, explaining that the training begins with players being led through a primer of the situation in Somalia and the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) mission, the country and peacekeeping context for which the game was created. Players then encounter a series of interactions with child soldiers and make choices that lead to varying results.

“The game leads you through these different situations where you see a child soldier and interact with them and you’re choosing which dialogue to go with,” Mimi says. “Depending on your choices, you might end up making the child angry and you’ll lose the game.

“It’s up to you whether you want to be heavy-handed or mild. As you go along, you learn which ways are the best.”

Mimi believes that this kind of interactive learning can be of unique benefit for security sector actors.

“It doesn’t take too long to play, but it does give you a quick feel for those situations,” she says. “It’s content that people in these organizations need to learn. And maybe it’s an easier way to take that information in than reading a huge document.”

Making an impact

Although originally designed to apply to Somalia and the AMISOM peacekeeping mission, student game developers have added functionality that allows users in different countries to alter the settings and game play to suit other nations. “Whoever’s working with the Romeo Dallaire Child Soldiers Initiative can customize it depending on what they need it to be at the time,” Mimi says.

Josh Boyter, communications officer for the Romeo Dallaire Child Soldiers Initiative, says students like Mimi have created a meaningful piece of a larger plan to address this challenge to the international community.

“Working together on the game project, we have created a student-developed tool that will have a direct impact on the work the Dallaire Initiative does around the globe to prevent the use of children as weapons of war” says Boyter.

Mimi says the game should be ready to deploy this month, wrapping up a project for which she was just one of many student contributors. Along with practical technical experience and the chance to work with the Dallaire Initiative, she and her colleagues gained the satisfaction of creating something that can make an important impact across the globe.

“It’s a global project in a lot of ways,’ she says. “It’s a game, but we didn’t want to make it trivial. We wanted to make it useful.”