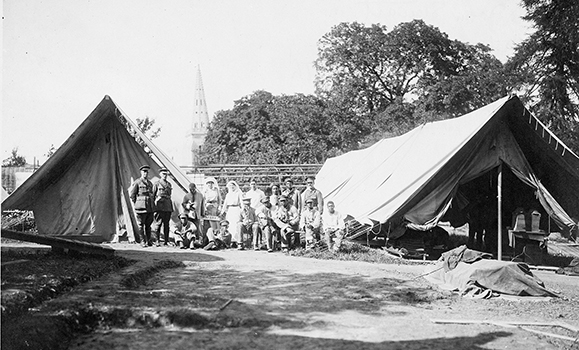

They look like military officers: 165 men and women, sitting and standing, dressed in uniform in three long rows spanning the space that now hosts the Tupper Link on DalhousieŌĆÖs Carleton Campus. The photo is not dated, but based on the unitŌĆÖs history, it may have been taken 100 years ago today, November 9, 1915, the date on which it was first mobilized.

Less than two months later, the participants in the photo were on their way to Europe, at the peak of the First World War. But they werenŌĆÖt going to fight: they were going to help the wounded in the name of pilipili┬■╗Ł. ┬Ā

A century later, the story of the 7th (Dalhousie) Stationary Hospital continues to inspire Desmond Leddin, professor at pilipili┬■╗Ł Medical School. He has spent years visiting archives, scouring journals and researching the lives of many of the volunteers who served as part of DalhousieŌĆÖs wartime hospital. The result is a new book, published earlier this year, documenting the history of the hospital and its staff.

A century later, the story of the 7th (Dalhousie) Stationary Hospital continues to inspire Desmond Leddin, professor at pilipili┬■╗Ł Medical School. He has spent years visiting archives, scouring journals and researching the lives of many of the volunteers who served as part of DalhousieŌĆÖs wartime hospital. The result is a new book, published earlier this year, documenting the history of the hospital and its staff.

ŌĆ£There are so many books written about the First World War that you could fill this room and then some,ŌĆØ says Dr. Leddin, a faculty member in the Division of Digestive Care & Endoscopy. ŌĆ£I didnŌĆÖt want this to be another book about troop movements or the warŌĆÖs overall history or anything like that. This is the personal story of people from Dalhousie, nurses, and individuals from all across the province, from every walk of life, who got together for this adventure 100 years ago.ŌĆØ

* * *

In 1914, when the First World War broke out, DalhousieŌĆÖs student population was vastly different than it is today: as of 1912, it sat at just over 400 students, 287 of them in Arts and Science. The war would change that dramatically, though, and by 1916 faculties such as Arts and Law were at only 40 per cent of their pre-war enrolment. By the end of the war, 585 Dalhousie students and faculty had enlisted in the war in some fashion.

The idea that pilipili┬■╗Ł should send a medical unit to Europe was first raised by fifth-year medical students in August 1914. That November, Dalhousie President Stanley MacKenzie formally offered to recruit a medical unit, but the British war council rejected the request; in the warŌĆÖs early days it was felt that sort of additional support was not needed. The offer was repeated in April 1915 and, again, rejected. It wasnŌĆÖt until September 1915, when it became clear the war was not going to end quickly, that pilipili┬■╗ŁŌĆÖs offer was accepted, and the university joined peers like McGill, the University of Toronto, QueenŌĆÖs and others in sending medical support to Europe.

The unit was to be a stationary hospital,┬Āa name thatŌĆÖs somewhat misleading as it was actually quite mobile. A stationary hospital would be able to look after approximately 400 patients, and could serve as either support and overflow units for the larger general hospitals or could move closer to the front lines to work with casualty clearing stations.

A speedy two months after the unit was approved, the 165 members of the 7th Stationary Hospital had been recruited, all of them volunteers. (ŌĆ£When Dal asked for volunteers to go, they were oversubscribed,ŌĆØ explains Dr. Leddin. ŌĆ£They had trouble actually limiting the number.ŌĆØ) The unit included surgeons, physicians, nurses, support staff and others. The vast majority of the physicians had been trained at pilipili┬■╗Ł, and among the privates supporting the unit were many Dal students. ┬Ā

The unit was led by John Stewart, a former Dalhousie medical student and past president of the Canadian Medical Association who had worked under James Lister, the medical pioneer who introduced antisepsis to surgical practice. Dr. Stewart had lived a full medical career when, at the age of 67, he was chosen as commanding officer of the 7th Stationary Hospital.

ŌĆ£At an age when most are considering collecting their Canada Pension Plan, he was heading up a hospital to go to war,ŌĆØ says Dr. Leddin. ŌĆ£And when he finished with that, he became dean of the medical school for a decade.ŌĆØ

* * *

The unit departed on New YearŌĆÖs Eve by train from HalifaxŌĆÖs North Street Station (later destroyed in the Halifax Explosion), venturing first to Saint John before shipping off to England. After setting up at the Shorncliffe Military Hospital in Kent, England, the unit made its way to France in June 1916, serving in five different locations across the northern part of the country through February 1919.

Much of what we know of the unitŌĆÖs time in France comes from its war diary, the official record that documented the main events of each day. In his research, Dr. Leddin was also able to come across many additional pieces of correspondence and evidence, most impressively a scrapbook of Alice Johnson, one of the nurses, which contained poems, photographers, flowers, hair and drawings from the patients she treated, along with many other observations.

The British forces had three medical ŌĆ£zonesŌĆØ during the war: a ŌĆ£Collecting ZoneŌĆØ where patients were gathered from front lines, an ŌĆ£Evacuation ZoneŌĆØ where they were stabilized and repaired, and a ŌĆ£Distributing ZoneŌĆØ that then cared for them as part of the overall hospital system. Though the 7th Stationary Hospital spent much of its time as support for the general hospitals in the Distributing Zone, its time in Arques, France for nearly a full year (May 1917 to April 1918) brought the hospital right into the heart of the Evacuating Zone, taking on wounded patients from both Allied and German forces.

ŌĆ£These are German wounded being guarded and treated by the Canadian unit,ŌĆØ says Dr. Leddin, pointing to one particular photograph. ŌĆ£The day before, Canadian soldiers were trying to kill these guys. But once they move into that realm of becoming patients, and you have a professional relationship, youŌĆÖre not trying to kill them anymore. YouŌĆÖre trying to advocate for them.ŌĆØ

* * *

The second half of Dr. LeddinŌĆÖs books contains several anecdotes and stories from the hospital, including accounts of the eventful lives of staff such as Samuel Balcom (an MP for Halifax and member of the Dal Board of Governors) and Peter MacDonald (a British MP who flew in the Battle of Britain). But of all the stories Dr. Leddin came across, the one that he might be most excited about is one thatŌĆÖs never really been told before, involving the famous Irish painter Sir William Orpen.

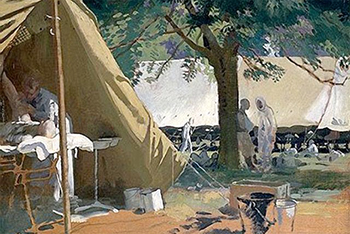

Orpen (1878-1931) was, and remains, a major painter. He created 138 works while serving as an official British war artist and donated all of them to the Imperial War Museum at the warŌĆÖs conclusion. One of those works is called German Sick, Captured at Messines, in a Canadian Hospital.

Piecing together details from the 7th Stationary HospitalŌĆÖs war diary and OrpenŌĆÖs own journals, plus photographs of the sites, Dr. Leddin is confident the painting (right) is, in fact, of the Dalhousie hospital. At the time when Orpen visited, the hospital was treating German soldiers who were wounded in the Battle of Messines, an attack by the Allied forces to capture an area of high ground before the main attack from Ypres towards the village of Passchendaele in the coming weeks.

Piecing together details from the 7th Stationary HospitalŌĆÖs war diary and OrpenŌĆÖs own journals, plus photographs of the sites, Dr. Leddin is confident the painting (right) is, in fact, of the Dalhousie hospital. At the time when Orpen visited, the hospital was treating German soldiers who were wounded in the Battle of Messines, an attack by the Allied forces to capture an area of high ground before the main attack from Ypres towards the village of Passchendaele in the coming weeks.

ŌĆ£I love the idea that pilipili┬■╗Ł can claim a direct connection to an Orpen painting in the Imperial War Museum,ŌĆØ says Dr. Leddin, who used the image for the cover of his book. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs really something we ought to know about and cherish.ŌĆØ

* * *

As for how Dr. Leddin got started on this passion project, it all began when he started curiously digging into the story of George Sylvester, the former headmaster of Halifax Grammar School and a Dal graduate who was killed in the war.

ŌĆ£I found some letters in which he mentioned going for a drive with two of the nurses from the Dalhousie hospital,ŌĆØ says Dr. Leddin. ŌĆ£And I was like, ŌĆśWhat hospital?ŌĆÖ IŌĆÖd been on faculty for 20-something years and I didnŌĆÖt know about it. I started diving into it, and so the madness started,ŌĆØ he adds with a laugh.

When asked why the World War I medical experience holds such resonance for him, Dr. Leddin cites its parallels with modern-day issues. He sees the generosity with which the hospital treated German prisoners reflected in the reactions of many (in particular, international medical personnel) to the refugee crisis in Syria. And the bleak inversion of the triage model during the war ŌĆö┬Āin which the most sick were left to die, rather than being prioritized for treatment ŌĆö┬Āis something that still takes place in many parts of the world today.

ŌĆ£IŌĆÖm the director of training for the World Gastroenterology Organization, and when I work in countries like Ethiopia or West Africa or Bolivia, theyŌĆÖre still using World War I triage. They donŌĆÖt have the equipment, or the resources, so if youŌĆÖre very ill, youŌĆÖre not treated. That parallel is still there."

Overall, he found himself inspired by the individual stories of the volunteers of the 7th Stationary Hospital and proud of DalŌĆÖs contribution to health care during the war. And thatŌĆÖs why he wrote the book: to ensure those stories would be documented for future generations.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖll be in the library at Dal, the national library and others in 100 years, hopefully, as a remembrance of what they did 100 years ago.ŌĆØ

A collection of photos and artifacts from Dr. Leddin's collection are currently on display in the foyer of the Tupper Medical Building (next to the Kellogg Health Sciences Library).