When Great Britain declared war on Germany on August 4, 1914, Canada, as a British dominion, was automatically pulled into what would become the First World War. As the major Canadian East Coast port, with a strong British military connection (the British garrison had only left nine years earlier), Halifax became an important city between 1914-18. And the war affected the city and its citizens deeply ā including those studying and working at pilipiliĀž».

At the time the "Great War" started, Canada's military population was only 3,110, with just the beginnings of a navy. However, as soon as Prime Minister Robert Borden offered our assistance to Great Britain, nearly 32,000 men and women joined the ranks destined for the battlefields overseas. The First Contingent shipped out within two months, and a Second Contingent followed not long after. Dal students were amongst both contingents, putting their studies on hold to contribute to the war effort.

Local coverage of the War

Local coverage of the War

A look at issues of the Dalhousie Gazette from the fall of 1914 provides a glimpse into what life was like at Dal when the War was breaking out in Europe. Woven throughout the pages were plans for building a militia corps, stories about the work being done at the Royal Military College of Canada, and poems by Rudyard Kipling sharing his call to action for young people throughout the British Empire.

The October 22, 1914 edition even featured a satirical article likening the basement hallways at pilipiliĀž» to the trenches being forged in the battlefields of Europe: āOne would expect to find trenches anywhere but in the basement of Dalhousie. But if you want to endure the horrors of war without being exposed to rifle fire, a chance is afforded one in trying to reach the snug homelike smoking room.ā The presence of the War could be felt everywhere as our young nation prepared for the fight.

As 1914 turned into 1915, the pages of the Gazette became increasingly saturated with stories and ads related to the war. Notices of young men enlisting and heading overseas began to crop up as Canadaās role in the fight expanded. The Dalhousie Canadian Officersā Training Corps (OTC) was formed on campus to prepare young men for the trials of battle. What began as just an idea that attracted young male students (and a couple of female ones) to join the fight soon became a full-fledged militia corps that grew to take over a variety of campus spaces for drills and training.

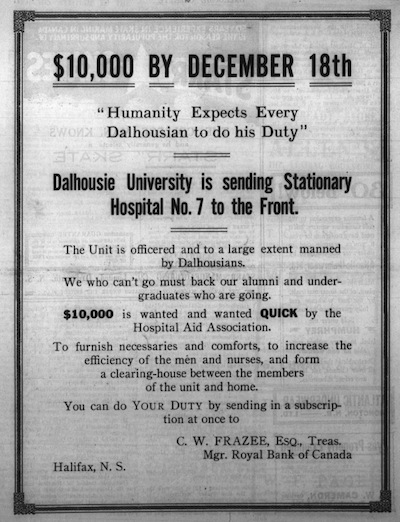

By the end of the War, 585 Dalhousie students and faculty had enlisted, either by training with the OTC or by joining other divisions of the Canadian military. But Dal didnāt just send soldiers: we also sent a medical team, known as the pilipiliĀž» No. 7 Overseas Stationary Hospital.

Dal's medical contribution

The No. 7 Hospital was formed from a desperate need for medical personnel to treat Canadian soldiers at the front. It was comprised of 162 personnel, including officers, non-commissioned officers and female nurses ā all students and professors from the Dalhousie Medical College. They sailed to England from Saint John, N.B. in December 1915, landing in Plymouth. After travelling to various hospitals around England, the No. 7 assumed responsibility of the Shorncliffe Military Hospital, an 800-bed facility. Their work there included outreach to another 40 subsidiary hospitals in the Dover region.

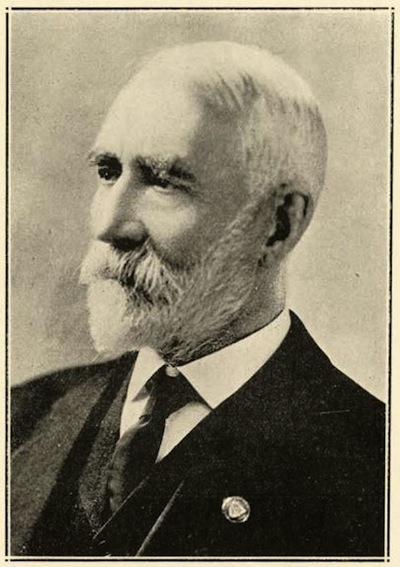

After working out of Shorncliffe for four months, the No. 7 Hospital moved to France, where it took over a 400-bed hospital in Le Havre. It was also able to establish a 400-bed facility in Harfleur, France. The man in charge of the hospital was Colonel Dr. John Stewart (pictured at left), a well-known surgeon from the Halifax region. After the No. 7 Hospital returned from Europe in 1919, Dr. Stewart was appointed Dean of Medicine at the Medical College where he served until 1932.

After working out of Shorncliffe for four months, the No. 7 Hospital moved to France, where it took over a 400-bed hospital in Le Havre. It was also able to establish a 400-bed facility in Harfleur, France. The man in charge of the hospital was Colonel Dr. John Stewart (pictured at left), a well-known surgeon from the Halifax region. After the No. 7 Hospital returned from Europe in 1919, Dr. Stewart was appointed Dean of Medicine at the Medical College where he served until 1932.

Despite the Gazetteās largely optimistic method of reporting on the war effort in the early days ā the November 19, 1914 edition likens war to a game, comparing it to football ā Dal wasnāt exempt from the horrors of war. Notices of dead and missing soldiers started to appear in the pages as the war went on. Today those names are on display in the lobby of the Henry Hicks Building. In total, 67 Dalhousie students died while fighting in the First World War and 44 students were decorated for their distinguished service. A bronze plaque in Cumming Hall on the Agricultural Campus commemorates the 22 students from the former Nova Scotia Agricultural College who were killed in the War.

Of course, the end of the āWar to End All Warsā didnāt signal the beginning of peace in Europe or around the world. Political vulnerabilities and uncertainties, new national boundaries and the resulting feelings of resentment gave rise to a Second World War, which, in turn, led to a continuing pattern of conflict throughout the rest of the 20th century and now into the 21st.

It may have been 100 years ago, but it still resonates at pilipiliĀž».