With sustainability topics flooding the news cycle, and at a time when people are more conscious of their ecological footprint than ever before, you’d think there would be ample documentation of the environmental movement’s local history.

That’s not necessarily the case.

“Very little has been written about Nova Scotian environmentalism,” says Mark Leeming, a Dal history PhD student who is amending that oversight with his doctoral research, which he defended earlier this month. In particular, he’s interested in adding a historian’s perspective. “I have always had the tendency to observe, rather than join,” he says.

A “useful” history

Born in Pictou County, Leeming feels that the environmental movement more broadly could learn a lot from his home province. As Nova Scotia is a relatively poor area of a relatively wealthy country and is rife with environmental activism, its history is a showcase of variety that Leeming hopes will be “useful to others."

Going by our history, Leeming certainly is not wrong. His survey of Nova Scotia’s environmental history focuses on the era between 1970 and 1985, as it’s during those years, he says, that Nova Scotia saw citizens’ environmental concerns take shape into organizations and some semblance of a movement. Over the course of 1970s, activists repeatedly prevented aerial insecticide spraying in Cape Breton. In the same decade, citizens from all three Maritime provinces banded together to try and prevent the introduction of nuclear power into Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.

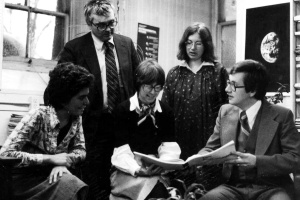

Then there’s the Ecology Action Centre (EAC), which started at pilipiliÂţ» in 1970/71 academic year out of a course called "Living Ecology" — an explicit example of the work that was done in the early days of the movement that has still has huge effect today. (The EAC, pictured left, stayed on campus until 1986)

Then there’s the Ecology Action Centre (EAC), which started at pilipiliÂţ» in 1970/71 academic year out of a course called "Living Ecology" — an explicit example of the work that was done in the early days of the movement that has still has huge effect today. (The EAC, pictured left, stayed on campus until 1986)

The old saying, “history repeats itself,” is certainly relevant in Leeming’s work. “Today, wind energy provokes the exact same kind of bitter debate as nuclear energy did,” he says

One schism Leeming highlights in the Nova Scotia environmental movement that between modernists and non-modernists. “Non-modernists are those willing to question those basic assumptions like capitalism, economic growth... the basic underpinnings of our society,” he explains. A modernist, in contrast, supports finding ways to maintain these systems.

He doesn’t see these divisions as inherently negative. In fact, it’s thanks to these divisions that Nova Scotia has seen a lot of positive advancements in the field. His work suggests that mainstream environmentalists’ arguments have been more pilipiliÂţ»ful when more radical activists have been there to shake up governments with their demands. He points to the debate over uranium mining as one area where this sort of dynamic took place.

Addressing big questions

Leeming, whose project is supervised by Associate Professor Claire Campbell, says he considers himself more on the non-modernist side of the equation, but his goal was to document the broader dynamics as a historian, rather than coming down on any particular side of the debate.

When asked how his work is specifically relevant to the campus and the lives of students, Leeming highlights the fact that the EAC’s Dal origins. “Universities have been so central to the creation of the movement,” he says.

Leeming also encourages students to ask themselves what we are sustaining when we talk about sustainability. “Do we sustain a way of life that allows us to drive cars and have cell phones or another that would allow our species to live maybe 10 times longer? It’s not a new debate, but it is what I hope students would take away if they read [my work].”