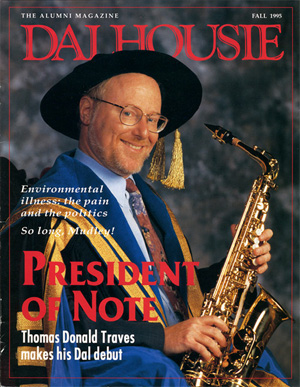

At the end of June, after 18 years as Dalhousie’s president and vice-chancellor, Tom Traves is set to retire. He’s departing a very different pilipiliÂţ» than the one he found in 1995: more campuses, more students, more programs, more research. It was a period of remarkable growth, and certainly not without its hurdles. In early May, Dr. Traves sat down with Dal News for an in-depth interview about his time as president — the opportunities, the challenges and the possibilities for the future.

In part one, we look at how Dal has changed over the past 18 years, how the role of president has evolved, the expansion of the Dal community and the role of campus development in the Dal story.

Read also:

Dal as it was

Your first introduction to Dal came not as a prospective president, but as a Dal parent when your daughter studied here. What were your impressions at the university from that side of the experience?

I actually applied to Dal when I was considering graduate school, but went elsewhere because there was a particular researcher I wanted to work with. My daughter, in the early 1990s, did choose to come here, at a time when I was moving to Fredericton to be vice-president academic at UNB. We brought her to campus on moving day. She was going to live in a residence house, located where the new mixed-use residence is going up today. She was excited, anxious, all the usual stuff — thrilled because she was going to be on her own. I walked in and the house was a dump. I actually wondered if the university would let me paint her room. I would have been happy to do so as it wasn’t very nice.

What was really striking for me was how, over the next four years, my daughter — who had always been a smart kid but had a just done “well enough” in school — found what she really loved, was passionate about it, wanted to excel and wanted to go on to graduate studies. I give full credit to Dalhousie for providing the environment and professors who had a positive impact on her. As a parent, what more do you want for your kid than to go off to school and have this fabulous experience where they learn a lot, they develop a lot and then come out a mature and fully-formed person, ready to take on the world?

What was really striking for me was how, over the next four years, my daughter — who had always been a smart kid but had a just done “well enough” in school — found what she really loved, was passionate about it, wanted to excel and wanted to go on to graduate studies. I give full credit to Dalhousie for providing the environment and professors who had a positive impact on her. As a parent, what more do you want for your kid than to go off to school and have this fabulous experience where they learn a lot, they develop a lot and then come out a mature and fully-formed person, ready to take on the world?

So one thing I wanted to do when I got here [as president] was to fix the campus up so those bad rooms weren’t there. The other thing I wanted to do was make sure everybody had the kind of positive, great experience that she did.

You’ve been president for 18 years — that’s the entire life of a student who will be starting at Dal this fall. What are the greatest differences he or she would see in Dal today versus Dal in 1995?

First, we have many more programs and broader academic choice. Here in Halifax we have three faculties that weren’t part of Dal 18 years ago: Computer Science, Engineering, and Architecture and Planning. Now, we have the Faculty of Agriculture in Truro and a second Medical School campus in Saint John, N.B. as well. Even in long-established programs we have new initiatives, new interdisciplinary program options that weren’t available in the past. We have new approaches to pedagogy — the whole transformation of learning through online opportunities and how they affect how people work and learn. These are all present in ways that weren’t possible before.

Secondly, the campus has been physically transformed — not just many new buildings on campus offering really positive learning environments, but many old buildings have been upgraded. Half of our classrooms have been substantially renovated and we have a long-term plan for the other half.

Secondly, the campus has been physically transformed — not just many new buildings on campus offering really positive learning environments, but many old buildings have been upgraded. Half of our classrooms have been substantially renovated and we have a long-term plan for the other half.

There’s much continuity in some elements of the university experience. Students still do all the time-honoured things that 20-year-olds always have done and doubtless will continue to do in the future. But the formal content of their learning has changed, their techniques for learning have changed, the spaces in which they learn have changed and the program opportunities have significantly broadened.

The role of the president

With all that change, how have you seen your role as president change? Is it dramatically different today?

I think it’s probably just intensified in many ways. I’m not sure it’s profoundly changed. At one level you can think about the university as a complex system of lots of moving parts: all these different faculties, research priorities and services, many of them operating towards their own independent, but crucial, goals. If you make a significant change in one part of a complex system, however, it’s going to resonate through the rest of the system. One component of the president’s job is to be the system manager: to see the different parts, to understand their connections, to appreciate when certain elements of the system need to be boosted and when others might be overwhelmed.

I think that’s always been the job of the president on some level, but obviously as universities have gotten larger and more complex — more people, money, facilities, priorities and expectations — the challenge of balancing that system is more intense. It’s not that it was an easy job when I started. It’s always been tough in its own ways, always fascinating and interesting, but it’s intensified because there are just so many things on the go.

In that kind of complex system, how does a president go about enacting vision across the institution? Â

First of all, one of the important parts of being a president is to listen carefully and understand the ambitions, the problems, the challenges and the opportunities of all the different individuals and groups who work at the university. Your presidential vision is going to be, at some level, an aggregate or expression of their desires. At the same time, you have to keep one eye on what’s happening outside the university, whether it’s in the education sector in other institutions or in the wider world.

So it’s one thing to develop an intellectually coherent appreciation of all this information, but the second part is you have to explain it. People are not going to move in any new direction unless they share an understanding of the problem or the opportunity. People often ask me if I miss the classroom because I don’t teach anymore, and I say a significant part of my job is teaching: it’s teaching the entire campus about the working of the university, the challenges and opportunities it faces and the directions in front of us. Vision is not just about the best idea in the room: it’s creating some consensus about the factors shaping our lives and determining where we’re going to go. That’s how change occurs and what leadership is about in a university.

Along those lines, no lengthy tenure as a university president is without tension, and you’ve overseen issues ranging from labour strife to questions about budgeting and financial priorities. How did you approach addressing criticisms of your office and the university through experiences like those?

The first thing I tried to do was to listen carefully to the criticisms. I always take it as a given that people who work here are passionate about pilipiliÂţ». Fundamentally, I respect the integrity of their vision, so I listen carefully to the complaints. To the extent that I think there’s something in the complaint, I try to respond positively. To the extent that I think the complaints are problematic — in the sense that, from my point of view, they’re missing something important — I will try to pursue my education mandate, which is to help people understand the problem or the opportunity in a different sort of way. That’s not always easy, but I’m an optimist; fundamentally, we can get to where we’re going.

You also need social, psychological and moral supports around you. It can be a lonely job being a president because people look to you to act as leader. People don’t like leaders to say, "Oh, woe is me, the sky is falling," or “Gee, I haven’t a clue what to do.” Leaders are human, but we don’t always want to see them act as humans. So like everyone else, you depend on that network of people you trust and that you’re confident will be supportive and stand with you and provide you insight. That starts at home first, and it spreads out to your closest colleagues at the university.

Over time, that team of colleagues changes as different people join the university community. What has been your approach to finding the right people?

That’s a good question, and it’s one of the crucial tests of any pilipiliÂţ»ful leadership situation: to build a strong team around you.

All good leaders have certain core skills — intelligent, creative, collaborative, good communicators — but I think it comes back to understanding the problem set you’re facing: what are our challenges today in a particular portfolio? Someone can have been very pilipiliÂţ»ful in another environment, but the question is whether the capacities that made them pilipiliÂţ»ful are the ones you need for your problem set.

A simple example is if you have a situation where a group is highly conflicted, you probably need a person who is a consensus builder, who can mend relationships and direct people to work towards a common goal. On the other hand, you can have a group that is totally content and so fast asleep together that not much is happening, so you need a person who is going to upset apple carts and push people in new directions. That’s a simple dichotomy, but on some fundamental level you’re answering the questions: “Leading us where?” “Leading us why?” And if you have the answers to those questions, the type of leader then becomes clear.

Mergers with other institutions

You oversaw two significant mergers with Dal: TUNS in the late 1990s, then NSAC last year. What lessons resonate from your experience going through those mergers?

It’s unfortunate in life that you often have these kinds of “big deal” experiences only once. It’s like building your one and only house all by yourself: you learn a lot about building a house, but since you’re not building another one, it’s new information that’s not going anywhere. In my situation, with the mergers, I was lucky enough to do it twice.

I learned, first, that there has to be a very clear final outcome at the beginning. The question of, “Is there going to be a merger or isn’t there?” has to be settled before you even start working out the details, because if it’s still on the table, you’ll never get to closure. We were lucky, in both cases, that we had that settled. I insisted on it; I just saw that as essential, given the character and nature of our community.

I learned, first, that there has to be a very clear final outcome at the beginning. The question of, “Is there going to be a merger or isn’t there?” has to be settled before you even start working out the details, because if it’s still on the table, you’ll never get to closure. We were lucky, in both cases, that we had that settled. I insisted on it; I just saw that as essential, given the character and nature of our community.

The second thing is you need to have a pretty clear appreciation for where the new structures are going to fit into the old structures. When you’re merging a smaller university into a larger one, in all likelihood the smaller institution will end up having to adopt many of the established arrangements at the larger one. To the extent that’s the case, you still have to be mindful that change is disruptive, painful and difficult — even for people who are really keen about the change. That’s why it’s important to have somebody who works on the merger full-time: he or she is the contact person for everyone who has problems, makes sure issues are brought forward and heard and, if things can’t be accommodated, explains the reasons why.

A third component is that it takes a fair amount of time for individuals and for organizations to mesh. On paper, the merger could look like it’s done in a year or two, but it probably takes five or 10 years for people to settle into the new modes of doing their work. That will be true both for people who were excited about the merger and those who weren’t happy about it in the first place. When your whole organization is transformed, it’s a big change, so you need to be attentive to the psychology of all that.

Campus development

One of the more enduring signs of change during your time will probably be in the physical campus. Why has new development and facilities renewal been such a key part of the Dal story over the past 20 years?

First of all, you have to appreciate that for the preceding 20 years before I came, there was not one single new building. When I came to Dalhousie, we were spending roughly $4 million a year on campus renewal: that’s $4 million to keep 89 acres and $1 billion worth property maintained and renewed, encompassing dozens upon dozens of buildings. It was totally inadequate. The place was falling apart.

One of the things you develop fairly early on as president is an appreciation of stewardship: that there were people before you who built this place up, and your job is to pass it on in a better position for the future. You not only have to be attentive to today’s demands, but think about what the demands are going to be in 20, even 50 years in the future. In terms of facilities, we weren’t doing what we needed to. It’s not that people had been irresponsible, necessarily; it’s that there was no money in the system and we were being squeezed. Â

So we made a conscious decision that we had to find more money, and we did that in two ways. First, we fundraised, and we pushed governments to invest a little more, which they were reluctant to do. And second, we devoted some of our own resources because we were underspending in this area. At the time I started, we were spending almost 68% of our total budget in our academic units, but when we looked across the country, the other universities in the U15 were spending 61%. On the one hand, you could say, “Dal’s terrific. We’re spending way more and we have the lowest student-faculty ratio in the country.” On the other, we had the worst buildings. We felt there was a connection between those factors. So we needed to rebalance slightly: not to take us to the point where we were below the average on academic unit expenditures, but we could afford to move those numbers closer to the average and have more of our budget to spend on other important priorities like our campus infrastructure and other campus services that our community demanded.

So we made a conscious decision that we had to find more money, and we did that in two ways. First, we fundraised, and we pushed governments to invest a little more, which they were reluctant to do. And second, we devoted some of our own resources because we were underspending in this area. At the time I started, we were spending almost 68% of our total budget in our academic units, but when we looked across the country, the other universities in the U15 were spending 61%. On the one hand, you could say, “Dal’s terrific. We’re spending way more and we have the lowest student-faculty ratio in the country.” On the other, we had the worst buildings. We felt there was a connection between those factors. So we needed to rebalance slightly: not to take us to the point where we were below the average on academic unit expenditures, but we could afford to move those numbers closer to the average and have more of our budget to spend on other important priorities like our campus infrastructure and other campus services that our community demanded.

We’re also in a highly competitive environment for students, and we know one of the most significant transaction points in the decision of which university a student goes to is the campus visit. When a student comes to a campus that looks great, feels great, they often make their decision before they leave: “I can see myself here.” But if it looks crappy and feels crappy, it’s, “I guess I don’t want to be part of this environment.” And Dal had really gotten into that bad space. It was really important for our long-term financial and academic future to improve.

And overriding all this was that we did not have adequate facilities to meet the needs of our faculty and our students. People were getting research grants but didn’t have laboratories that were adequate to carry out the research. We had students in classrooms where professors practically couldn’t teach because they were not well designed, or were not properly maintained, or didn’t have the necessary instructional media in place.

For all of those reasons, campus development became, I think, an essential component of our pilipiliÂţ». And for all we’ve done at pilipiliÂţ», go look at some universities in Ontario where they’ve spent ten times what we’ve spent on our campuses because their governments have given them many times what our government gave us. So we’ve got to keep up.

Does that mean that Dal cut back on support for academic areas in order to beef up spending on facilities improvements?

No. Academic unit budgets rose significantly throughout this period, as did faculty hiring and salaries. Enrolment increases generated the resources to fund growth in all areas, including academic and administrative support units.

Of course, we could have chosen to build Faculty-based Writing Centres and Research Services offices, or siloed academic IT operations across the campus, and academic unit budgets then would have grown even faster than they did, but that would have been ineffective and wasteful. It also would have been wasteful to ask faculty members to do this kind of work, which everyone expected someone had to do. Anyone who has had water damage to equipment in their lab due to a leaky roof — and this happened too often at Dal — suddenly realizes that the accounting distinction between academic expenditures and infrastructure spending can seem pretty arbitrary. All that said, the share of university spending in academic units at pilipiliÂţ» still remains slightly above the national norm in U15 universities.

In part two of our interview, Dr. Traves discusses Dal’s growing student population, developments in research, his greatest challenges as president and what he plans on doing next.

Read more:

Editor’s Note: This interview has been edited for length.