It’s a ravenous predator, leaving a path of destruction in its wake. But unlike many ocean predators that struggle in an aquarium setting, this one has only been found in captivity.

Until now.

Kate Rawlinson, a biology postdoctoral fellow at pilipiliÂţ» in Brian Hall's lab, is co-author of a paper published in PLoS ONE published this week documenting the first confirmed identification of Amakusaplana acroporae in the wild. The polyclad flatworm, known commonly as the AEFW (Acropora-eating flatworm), has become a notorious thorn in the side of aquaria enthusiasts.

“It’s been a problematic predator in coral aquariums for the past decade,” explains Dr. Rawlinson. “It eats Acropora corals, can destroy entire colonies and is very hard to get rid of.”

Small, hard to detect

Researchers always believed that the species originally came from the ocean, entering the aquarium trade on fragments of coral from the reef or from coral farms, and passed between growers as they share fragments to grow new reefs.

“But no one had ever seen it in the wild,” adds Dr. Rawlinson. A big reason for that is its size: ranging from 4 milimetres to 2 centimetres, it’s extremely hard to see with the naked eye.

“It is small and very well-camouflaged... it is easily transported between aquaria without detection.”

Dr. Rawlinson was part of the team that gave the AEFW its formal scientific name, and was eager to see if it could be located in its natural habitat. She found a willing partner in Jessica Stella, a PhD candidate at James Cook University in Australia and an expert in invertebrate fauna in coral reefs. Together, they looked at some unidentified specimens and, following Dr. Rawlinson’s molecular analysis, confirmed that they had found what they were looking for.

Finding a biological control

The discovery actually brings forth more questions than answers. To start, while they know the flatworm feeds on coral in the wild, they’re not yet certain if it causes the same type of catastrophic damage as it does in captivity. They suspect that it might have natural predators – and figuring out what those are could be incredibly important to stopping the flatworm’s spread in captivity.

“This sets the stage for future research on its impact on wild reefs – and also to identify biological controls that could be used to combat problematic infestations in aquaria.”

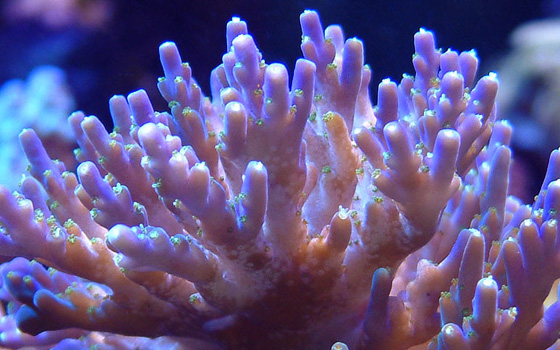

A reef damaged by the AEFW. (Marc Levenson photo)

A reef damaged by the AEFW. (Marc Levenson photo)