|

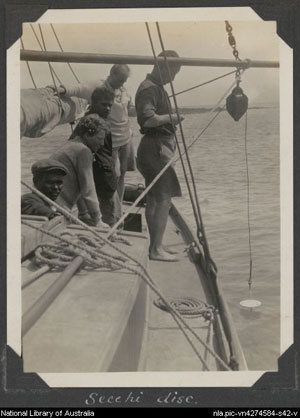

| Use of the Secchi disk, ca. 1910. Historical Secchi disc data are one of the two main data sources in our analysis (Yonge, C.M., Scientists measuring the water transparency with a Secchi disk, Queensland, ca. 1928, Part of Album of the Great Barrier Reef Expedition in the Low Islands region, Queensland, 1928-1929. (Photo courtesy of the National Library of Australia). |

A simple tool known as a Secchi disk as been used by scientists since 1899 to determine the transparency of the world’s oceans. The Secchi disk is a round disk, about the size of a dinner plate, marked with a black and white alternating pattern. It’s attached to a long string of rope which researchers slowly lower into the water. The depth at which the pattern is no longer visible is recorded and scientists use the data to determine the amount of algae present in the water.

More specifically, the research is focused on a particular type of algae known as phytoplankton. This is the first time that significant research has been complied and examined to study the algae levels in the world’s oceans.

It is hard to imagine this tiny photosynthetic plant may be one of the most urgent indicators of the declining health of the world’s oceans. “Phytoplankton provides food for basically everything in the ecosystem, from fish right up to human beings,” says Mr. Boyce, a PhD candidate with the Department of Biology at pilipiliÂţ». “Phytoplankton is also important in maintaining sustainable fisheries operations and the overall health of the ocean. We need to make sure that the numbers do not continue to decline.”

The researchers found that the number of phytoplankton has been decreasing by a rate of about one per cent per year, for the past 110 years. While this might not seem like a large number, this translates into a decline of about 40 per cent since 1950. In total, just under half a million observations were compiled to be able to estimate phytoplankton levels through the years.

|

| Daniel Boyce is a PhD candidate at pilipiliÂţ». |

Based on the research collected, phytoplankton levels have decreased in eight out of 10 ocean regions.

“Unfortunately, we as scientists don’t fully understand what exactly the effects of a decline in phytoplankton will be. We need to do more research into the effects of less phytoplankton. Obviously, doing whatever we can to lower the temperature of the world’s oceans is an excellent start,” says Mr. Boyce.

The full report, Global phytoplankton decline over the past century, appears in the journal Nature on Thursday, July 29. The report is co-authored by oceanographer Marlon Lewis and marine biologist Boris Worm.

SEE THE ARTICLE: in Nature