|

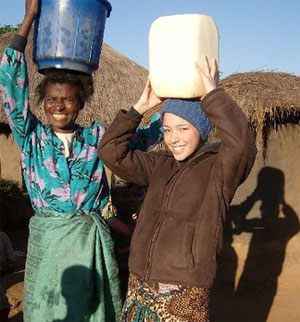

| Dalhousie science student Emily Stewart is a volunteer in Malawi with Engineers Without Borders. |

âMalawi ⊠I think Iâve heard of that. Didnât, like, Madonna adopt a baby from there or something?â

That was usually the first response Dal student Emily Stewart would get when she'd tell people she was going to Malawi as a volunteer with Engineers Without Borders Canada. She knew little more herself, aside that the country was landlocked, nestled between Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia in southern Africa, and had a lake almost one-third its total area.

But since May, the young woman from White Rock, B.C. has been gaining an intimate understanding of the impoverished country. So far, her experience has been eye-opening and exhausting. Sheâs been wrapping her tongue around the Chichewa language, rebuffing marriage proposals and bathing in four cups of warm water. There have been bouts of explosive diarrhea and unexplainable tears. Plus, sheâs had to get used to being the centre of attention almost all the time.

PHOTO ESSAY: 'The air smells alive'

âThatâs the toughest thing,â she writes in an email to Dalnews, âThe respect and privilege I get as a mzungu (white person/foreigner) is not something I feel I deserve in the least.â

But at the same time, sheâs never learned so much, from how to adapt to a new diet and living conditions to communicating using a Chichewa phrase book, lots of hand gestures and plenty of good humor. Everything is markedly different from her life as a Dalhousie science student. Until now, one of the biggest challenges sheâs had to face is deciding what to focus on in her second year: microbiology and immunology or economics?

Engineers Without Borders, by the way, isnât limited to engineering students. Volunteers come from different academic disciplines, including international development studies, science, environmental studies, theatre. EWB volunteers are currently working in four countries: Burkina Faso, Malawi, Zambia and Ghana. Some, like Ms. Stewart, are on four-month junior fellowship placements while others are on long-term overseas placements ranging from one to three years. Many Canadian universities have chapters of EWB, including Dalhousie.

She done things she never could have imagined. Despite being a vegetarian, sheâs sampled offal (ârhymes with âawfulââ), a deep fried assortment of goat heart, liver, stomach, and large intestines. And, early on in her stay, she was enlisted by a blind midwife to deliver a baby.

âI entered the dark hut and was immediately struck with a metallic odour I couldnât quite put my finger on,â she recounts on her blog (.) âAmayi gave me a pair of XL plastic gloves and told me to close my eyes. âSo you be blind like me,â she explained. Closing my eyes didn't make much difference as the hut was almost pitch dark in the middle of the afternoon. But I closed my eyes, and let Amayi take over. She took my hand and my finger and placed it somewhere as I heard a quiet moan. âThat is head of the baby,â she told me in her limited English as the tip of my finger poked an indescribable surface.

âI was in such shock that the next 20 minutes passed by without much thought. The birth was surprisingly muted and happened very fast (unlike how movies make them out to be); the woman giving birth (named Melissiana) was silent except for an occasional quiet groan. But the most shocking part came after, when I realized I had delivered the baby myself. Amayi had simply stood at the head of the bed, supporting the womanâs head in her arms, while I stayed at the other end and pulled the curly-haired baby out.â

As a volunteer with Engineers Without Borders, Ms. Stewart works with Concern Universal, a non-governmental organization that works to alleviate poverty in rural communities. Specifically, sheâs been monitoring and evaluating how the organization's water and sanitation projects are workingâwhether disease prevalence has been decreasing because of better hand washing and covers that keep shallow wells from becoming nesting grounds for mosquitoes.

There is usually a technical component to the projects EWB volunteers work on. In Burkino Faso and Ghana, for example, volunteers are refining whatâs called a âmultifunctional platform.â Itâs basically a diesel engine mounted on a steel chassis that powers a variety of end-use equipment such as grinding mills, de-huskers, battery chargers and water pumps. The idea is to help women with many of the tasks they do by hand: pounding cassava, grating gari and grinding grains.

Ms. Stewartâs work with EWB will continue when she returns to Canada: âMy goal is to learn as much as I can about poverty and development ... Whether itâs learning to be more critical about development initiatives, or simply promoting development among family, friends, community and government, I'm going to share my experience.â

LINKS: |

READ:

Malawi at a glance

Malawi, a landlocked country in southern Africa, is among the world's poorest countries. Of its more than 12 million people the vast majority live in rural communities, with only 16 per cent living in urban areas such as the cities of Lilongwe and Blantyre. The remainder live in rural areas where the population density is one of Africa's highestâsix times that of neighbouring Zambia. This, coupled with rapid population growth and erosion due to deforestation, is applying severe pressure to the agricultural industry which employs the vast majority of the population. Malawi's economy is based largely on agriculture, which accounts for more than 90 per cent of its export earnings and 45 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP). Malawi has some of the most fertile land in the region and almost 70 per cent of agricultural produce comes from small-scale farmers. However, land distribution is heavily unequal, with more than 40 per cent of smallholder households cultivating less than 0.5 hectares. Access to water and sanitation is also unequal, with an estimated 57 per cent of the rural population with access to safe water in comparison to 90 per cent of the urban population. Access to sanitation is considerably lower with only 15 to 30 per cent of the rural population having access to a latrine. As a result water-related diseases, including cholera and typhoid, are common; a problem exacerbated by the rapid spread of HIV/AIDS. Almost half of the population is under 15 years old and many of these are orphans. (Source: Engineers Without Borders) |