|

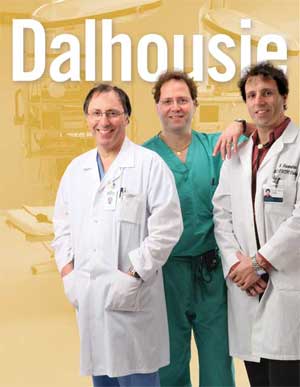

| Mike, Carman and Nick Giacomantonio on the cover of Dalhousie Magazine. |

Whatās a big brother for anyway? When Carman Giacomantonio told his older brother Mike he wanted to go to university and then on to veterinarian college, Mikeās reaction went kind of like this:

āWhy would you want to take care of dogs when you can take care of people?ā

A few years later, Nicholas gave big bro Mike a call as well. Like Carman, Nick, then a mechanic, was seeking the blessing of the first person in the family to go into medicine.

āSo I called Mike,ā recounts Nick. āAnd he says, āWhy would you ever want to be a doctor when you could be a great mechanic?ā

Gathered in Carmanās office in the old Victoria General Hospital in Halifax, the three brothers ā Mike, 58, Carman, 49, and Nick, 46 ā share a laugh at the remembrance. Mike protests he wanted Nick to be sure he was making the right choice; Nick says Mike liked having someone handy to fix his fancy cars.

After a few detours, Carman and Nick eventually did stumble onto the path Mike had blazed, from Whitney Pier to med school and on to pilipiliĀž»ful medical and teaching careers. Mike (BSc ā71, MD ā76, PGM ā81) is a surgeon. Heās the chief of the Division of Pediatric Surgery at the IWK Health Centre in Halifax and associate professor of surgery at pilipiliĀž». Carman (BSc ā87, PGM ā97, MSC ā98) is an oncologist. Heās the head of Nova Scotiaās Surgical Oncology Network, an associate professor of surgery at pilipiliĀž» and the clinical head of the recently announced breast health clinic at the IWK Health Centre. Nick (BSc ā87, PGM ā98) is a cardiologist. Heās the director of cardiac rehabilitation for the Capital District Health Authority and assistant professor of medicine at pilipiliĀž». Heās also the founder of the Heartland Tour, an annual 1,000-kilometre bike tour he started last summer to talk about heart health in communities across Nova Scotia. There is another Giacomantonio brother ā 54-year-old Joe ā a pharmaceutical rep who lives and works in Cape Breton.

Tell by the socks

These days, the doctors share the same hard-to-pronounce seven-syllable surname, the same profession, live within two blocks of each other in Halifaxās south-end neighbourhood and drive Chevy Suburbans, their late dad Jimmyās vehicle of choice.

You can see their differences only by lifting their pant legs, jokes Mike. And sure enough their socks have tales to tell: Carman, the āheadstrong renegade,ā wears flashy argyles; Mike, who settles on ādeterminedā as his adjective (āHeadstrong has a level of energy I donāt have,ā he says dryly), sports cozy homemade hosiery; and Nick, the passionate one, wears red.

The four brothers grew up in hardscrabble Whitney Pier, a part of Sydney located on the east side of Sydney Harbour. Their parents were Italians, born of immigrants who arrived āin the Pierā at the turn of the last century to take up work at the steel plant. According to family lore, one of their grandfathers arrived in Boston Harbour and was offered a job by one of Al Caponeās men as soon as he got off the boat. Instead, he took the pearl-handled revolver given him and walked all the way to Cape Breton in search of more honorable employment. Generations of Giacomantonio kids have dug around the foundation of the garage in Whitney Pier, where the fabled revolver is reputedly buried.

Ģż

Located literally on the other side of the tracks, Whitney Pier in the 1950s and 60s was home to all kinds of people: Jewish, African, Ukrainian, Yugoslavian, Polish, Italian, Irish, English. Each ethnic community took care of its own, their worlds centred on their individual churches or synagogues. But the children all knew each other, playing in the middle of the street and on the moonscape left by the coke ovens. Moms and dads

and uncles and aunts sat and watched from front steps, smoking and talking in their different languages.

āIt was the perfect ghetto,ā says Mike. āI canāt overstate how rich it was. While it looked poor, it was anything but.ā

|

The Giacomantonios lived with one of their grandmothers in a tiny old house on Lingan Road and Uncle Ernie and his family lived right next door. Their dad, Jimmy, and their Uncle Mike eked out a living running a dry-cleaning shop in nearby New Waterford, a coal mining town where there was not a great demand for dry cleaning. Mike grew up speaking Italian, but their parents encouraged their boys to speak English so they might integrate better. Nick says he now knows only a few words in Italian ā ājust enough to get my face slappedā ā and is taking classes to learn.

Jimmy, who had shortened his last name to āMantonioā so customers could better remember it, was a warm and nurturing father. The sons describe their mom, Angie, as a pillar of strength and determination. A hard-working, intelligent woman, she declared her children would succeed ā or else. The brothers recalled how sheād arrange for one of their cousins to come over and give them pre-exams before real exams.

āAcademically, if we didnāt perform well in school, we would be killed,ā says Carman matter-of-factly.

At the top of Whitney Pierās social strata were the doctors and lawyers. Either of these, Angie decided, were suitable occupations for her sons.

āWe were brought up to go to university,ā says Mike, one leg crossed over the other to show a swath of home-made sock. āI remember going to school in Halifax and coming back, utterly homesick. My parents pleaded with me to stick it through. They were dedicated to my education. Stay there, they implored, something will kick in if only you stay.

'On a platter'

āI was the first. They handed everything to me on a platter.ā

Once Mike could officially put M.D. behind his last name ā he and his brothers reclaimed the missing letters g-i-a-c-o ā his mother was eager to set him up in the family home in Whitney Pier. She was ready to dedicate a room in the house for his practice, even to get a new phone line installed.

āShe was devastated when he didnāt come back to Whitney Pier,ā says Carman. āShe had the bureau all set up beside the captainās bed and promised the new phone.ā

āBut in the end, it was OK to leave,ā adds Mike, ābecause I was working at the childrenās hospital. That was pilipiliĀž» enough for her.ā

Meanwhile, Jimmy had died of lung cancer, no doubt because of his three-pack-a-day habit and the dry-cleaning chemicals he worked with. Carman and Nick, then 17 and 13, took their fatherās death hard. Without that stabilizing, loving influence in their lives, both boys on the cusp of adulthood spiraled out of control.

āYou couldnāt tell me to sit down and study,ā says Carman. āHe was the only one.ā After high school, Carman began studies at pilipiliĀž» but only lasted two years ā āI left by mutual agreement.ā Six months after leaving, he realized his mistake, but it took six years to return.

He finally graduated with a BSc (Biology) from pilipiliĀž» in 1987, with plans for going to Dalhousie Medical School afterwards.

'Keep us honest'

His dream was met with a road block, however. āI was told very clearly that I would not get in because I was nothing but a lazy joe,ā he recalls. Decades later, the words still sting. But he dusted himself off and applied to med school at Memorial University of Newfoundland, eventually returning to pilipiliĀž» to graduate with a degree in general surgery in 1997 and a masterās in pathology in 1998.

Now as teacher himself, itās those questioning students he relates to. He says he loves teaching because he learns so much.

āStudents provide honest feedback to their teachers. I personally take that very seriously. Senior students enjoy challenging us: they donāt accept dogma and protocol without evidence. They keep us honest.ā

As Carman was struggling to find his way, Nick too was kicking against authority; he was acting out and taking easy subjects at school to get by with minimal effort. As an Italian kid from Whitney Pier, he says, teachers didnāt expect him to amount to much and he wasnāt doing anything to make them change their minds. That is, until a flippant comment from a history teacher at graduation hit like a slap in the face and made him want to prove the naysayer wrong.

āHe says, āMantonio, the award for the trip to Fantasy Island goes to you, the guy most likely to go nowhere fast.ā Iāve never forgot it.ā

After high school, Nick went to trade school and got his mechanic licence. He was a pretty good mechanic, he says, but came to a realization he needed more of a challenge. He went back to high school to upgrade his marks and this time made the honours list. After getting his BSc (double honours, Microbiology and Biology) at pilipiliĀž» in 1987, he applied to Memorial University on Carmanās recommendation. He completed residency training in internal medicine and cardiology at pilipiliĀž».

Passion leads to action

Ģż

All three brothers agree, theyāve found their passion, no matter the route it took. While their dad may have been a dry cleaner, his conscientious example guides them as they respond to the needs of patients and students. Jimmy was honest, meticulous and took pride in a job well done.

āYou know that old saying, āitās in the giving that you receive?āā queries Mike. āWell, you know what? Iāll be damned if thatās not true. And then to get paid on top of that is really quite remarkable.ā

āThereās nothing better than the thanks you get from a patient and knowing that youāve helped,ā says Carman. He pulls open a desk draw stuffed with cards from people heās helped. Interacting with students, he adds, is also incredibly rewarding.

āYou do what youāre passionate about,ā adds Nick. āPersonally and professionally, itās passion that leads to action and action leads to change. So you just do what you know is right.ā