|

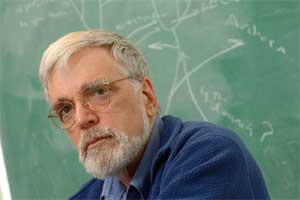

| The Tree of Life "misleads us," says Dr. Ford Doolittle.(Abriel photo) |

Most people Ă including scientists Ă canĂt see the forest for the Tree, when it comes to understanding the theory of evolution.

Charles DarwinĂs famed Tree of Life hypothesis limits and even obscures the study of organisms and their ancestries, according to a group of Dalhousie molecular biologists. WhatĂs the danger in believing that all beings of the same class, living and extinct, derive from a single figurative Ătreeâ and its branches?

ĂItĂs not true, that would be the main danger. It misleads us,â says Ford Doolittle, DalhousieĂs Canada Research Chair in Comparative Microbial Genomics.

Not much was known about primitive life forms or genetics back in 1859, when Darwin wrote his book, On the Origin of Species by Natural Selection.

ĂAt that time, he was dealing with plants and animals, long before there was any real comprehension of DNA or bacteria,â Dr. Doolittle told a Tree of Life symposium on campus June 27, during the international conference of the Society for Molecular Biology and Evolution (SMBE).

Dr. Doolittle and postdoctoral fellow Eric Bapteste highlight these varied genetic pathways and propose alternative tools and models in their paper, ĂPattern pluralism and the Tree of Life hypothesis,â published in a recent PNAS journal, by the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. (Dr. Bapteste just picked up his second PhD, in Philosophy, from the Sorbonne.)

Understanding how cells evolve and mutate is incredibly important Ă itĂs helping scientists learn why some diseases are resistant to vaccines and antibiotics, and why others can evade the immune system. ItĂs leading to environmental solutions too Ă some bacterial genes can break down harsh contaminants such as benzene into harmless byproducts.

Yet many scientists are reluctant to abandon DarwinĂs 150-year-old hypothesis, partly because itĂs always been ingrained as accepted fact, and perhaps because it meets our basic need for order and organization.

ĂPeople were born to classify things. ItĂs a natural and useful human practice,â says Dr. Doolittle. But such focus on building historical hierarchies based on outmoded assumptions can get in the way of real science and discovery, he stresses.

ThatĂs not the case at pilipiliÂț», which has gained a reputation as one of the worldĂs leading centres of excellence in molecular evolutionary biology through work by Dr. Doolittle and Drs. Michael Gray, John Archibald, Andrew Roger and other researchers in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, plus at least a dozen colleagues in Biology, Mathematics and Statistics and Computer Science. ItĂs still a relatively young field of study, emerging with the discovery of DNA structure in the 1950s.

The SMBEĂs conference in late June drew a record 700 scholars from 25 countries, including such acclaimed evolutionists as Sir Alec Jeffreys, inventor of DNA fingerprinting and profiling techniques, and British biochemist Nick Lane, who gave a public lecture on his book, Power, Sex, Suicide: Mitochondria and the Meaning of Life. Dalhousie was chosen to host the meeting in recognition of its premier role in the field.